Abbess Gantumur in her office, Tugsbayasgalant Mongolian Gelug Women’s Centre. 26 September 2008. Photograph: C Pleteshner

Throughout history, women have been written out

of cultural moments they helped shape. [1]

This vignette is of Natsagdorj Gantumur, one of Mongolian Guru Deva Rinpoche’s most high profile Khalkha Mongol students and devotees. She is also the Founding Abbess of Tugsbayasgalant Women’s Centre in Ulaanbaator. ‘Tugs‘, as it is affectionately referred to by women in Mongolia, is her project.

Regarding pseudonyms and present tense-ing

N.Gantumur expressed no objection to her patronymic and given name being revealed and has given me her permission to do so. However, I also think it important to add here, that the pseudonym allocated to Gantumur by other Mongolian women in our study was ‘Boldmaa’ or ‘Steel Mother.’ I carry these Mongolian women’s voices with me as I continue to write, migrating away from ‘the local’ across and into the cultural and linguistic divide. The pseudonym initially allocated by Mongolian women in Mongolia, says more about N.Gantumur than I ever could.

I have written Gantumur’s vignette [2] in the present tense so that it serves as a historical record—a ‘snapshot in time’ if you like—of what was happening, and of interest and concern in 2008. The Abbess’s own words and those of other Mongolian women are rendered in italicised script.

Post-socialist Mongolian Gelug Revitalisation: from the 1990s on to 2008

Gantumur is well-known in the social circles of Mongolia’s political and religious elite. She is to date the only Abbess (Tib., Hambo) of an indigenous institution associated with Mongolian Gelug Buddhism in Mongolia. Her husband is a Gelug lama too.[3] In cosmopolitan Ulaanbaator and its vibrant local ‘aristocracy of culture’ (Pierre Bourdieu 1984), Gantumur Hambo carries appreciable ‘capital’ in each of her cultural, religious and socially-situated spheres.

Her students, Mongolian and Buryat women who formally study Mongolian Gelug Buddhism according to her instructions and curriculum are highly regarded by the many women living in Ulaanbaator with whom I spoke. For it is to the Tugs Women’s Center that these women go to pray to Tara and where regular Tara liturgies and other pujas are publicly performed.

Mongolian Gelug ‘anis’ preparing for a Tara Puja. Tugsbaysgalant Women’s Centre, Main Puja Hall, Ulaanbaator. 21 Sept 2008. Photograph: C Pleteshner

Tugs is a Mongolian Gelug Buddhist Center in Mongolia where women of all ages, not infrequently accompanied by children in their care, go to obtain spiritual counselling and have a range of ‘traditional’ (read as: already being practiced in the family) divinations enacted by a Mongolian ani. Tugs is a local organisation run by Mongolian women for Mongolian women.

They come here for all sorts of personal reasons. They come to make offerings for the removal of obstacles to certain difficulties in their lives, or those of their family members or dear friends. There have been occasions where Mongolian women friends have sponsored a puja for me. In other locations, I have ‘sponsored’ similar rituals for others. With regard to this aspect of my narrative, I experience less of the emic/etic divide.

Mongolian Gelug ani, mother and daughter. Tugsbaysgalant Women’s Centre Ulaanbaator. 21 Sept 2008. Photograph: C Pleteshner

Here we see a Buddhist liturgy being recited by one of the Centre’s anis in response to a request from a Mongolian mother accompanied by her daughter. My data (cf. Mongolian women) tell me that, when we feel the need, we sometimes, spontaneously, make the decision and travel very long distances by bus, often alone, to request specialist religious services from anis at Tugsbaysgalant or attend pujas.[4] Others come here to make the traditional one hundred butter lamps offering for a family member who has recently passed.

A Tugsbayasgalant Women’s Centre ani preparing the traditional one hundred butter lamp offering. Ulaanbaator. 21 Sept 2008 Photograph: C Pleteshner

From little things, big things grow

After starting in a small ger, Tugsbayasgalant as an organisation has grown and is now situated on privately-owned not rented land located in the heart of Ulaanbaator near the main thoroughfare Peace Avenue. Gantumur is a lifelong devotee of the spiritual and a political leader of Mongolia’s Gelug Buddhist Church, Guru Deva Rinpoche who passed (from this life to the next) in 2009.[5] Establishing Tugsbayasgalant was her idea and with her Teacher’s support, she has guided the development of the Women’s Center from the outset.[6]

The facility, a new brick building, is now open and staffed by anis from 10 am in the morning every single day, seven days a week (2008). Mongolian women who visit the Center refer to Gantumur as Gantumur Hambo, and so as you see I too at times use this honorific title for her here. Women refer to the main room at Tugsbayasgalant, the room in which where most of the statues and thangkas are displayed and where Mongolian Buddhist rituals and offerings are performed for the public, as Ani Gompa. ‘Ani’ and ‘Gompa’ are Tibetan language terms.

A professional working life

Now in her 50s (in 2008) Gantumur was born in Buyant Sum in Khovd Aimag in Mongolia. Her parents moved to Ulaanbaatar City when she was a baby. After graduating from high school she went on to qualify as a Teacher of Mathematics from the State Pedagogical Institute. She then worked as a Teacher of Mathematics for two years. Between 1978 and 1980 she attended evening classes at the Political Institute and began working as an administrator.

From 1985 until 1990 she worked as Laboratory Manager at the State Pedagogical Institute’s Physics Department. In 1990, at the age of 39, and close to the time Mongolia was officially declared a Democratic Republic, Gantumur resigned from her paid administrator’s position to set up Tugsbayasgalant. [7]

N.Gantumur officially established the women’s Hural on the 2nd of October 1990. With its official registration and stamp, ‘Tugsbayasgalant’ was launched as an organisation. Gantumur, one of the ‘socialist era’ Mongolian women in my study, like many of her contemporaries also has six children of her own and (in 2008) has eight grandchildren.[8] What an incredibly busy, responsible and productive life!

A local belief system expressed in a ‘how it all started’ form

Gantumur speaks of how, rather than developing an interest in Buddhism, a Mongolian born from the womb breathes the purity of Buddha’s ‘soul’.[9] She speaks of how she became aware of her own strong belief in Buddhism at a very young age and of how she had inherited her own devotion to the Buddhist religion from the many earlier generations of Mongolians before her. She tells stories of how every time she would pass the Choijin Lama Temple in Ulaanbaator on the bus with her mother, as she went to work, and earlier as she was being taken to school, how she would feel excited at the very sight of the temple and the surrounding walled-precinct. As she recalls, I was then only five years old.

She also recounts how worried and anxious she was when she heard news of the Cold War (1947-1991) in foreign countries and their sudden calamities. She describes her preoccupation as being less to do with the politics, but more to do with the fate of people, particularly what would happen to my people if such a disaster happened in my own country.

Residual-s

As for the residual impact of Soviet socialism and its political rule on her Buddhist faith? Gantumur Hambo’s answer was straightforward, Although Mongolia developed atheism for about seventy years, there is nothing to prohibit the workings of one’s own mind. Things concerning one’s mind stay with one’s mind forever. If one develops a generous mind, no one can destroy it. The fruits of such generous minds managed to survive until 1990. So, here we are now.

I really respect and admire how Gantumur thinks! It seems consistent with her personal investment and belief in the Women’s Center to hear her say, women have more generous souls. She reflects on how, most people visiting the monasteries and temples in Mongolia are women, both before and after 1990. This is the basis upon which she has reasoned to think that a woman has a stronger mind and soul. And although father and mother equally love their children, there is nothing in this world to compare to a mother’s soul.

Goal No.1: Providing equal opportunity of expression in established situ

Gantumur Hambo is very clear about her personal goals. She considers that, women should have the right to recite puja [10] for the benefit of all sentient beings. She recounts stories about, rituals with the idea of discriminating against women such as prohibiting women’s practice, comparing her to a wolf sneaking up and into the fenced herd, and prohibiting women from climbing up certain mountains and high peaks.[11] These are what have galvanized her into, standing against such prohibitions, and instead, expressing the abilities and capacities of women.

Goal No.2: Establishing a Mongolian women’s ‘hural’ based on respect

Her second main goal was, to establish the hural. She reflects on how, women receive broad respect from others on the basis of their kindness, humbleness, moral purity and their own respect for others. She also commented on how, from the very beginning I thought that a woman has the right to practice Buddhism. But in the process of my activities, I learnt that Buddha taught that everybody, not depending on their sex, is equal in receiving Buddha’s teachings and reaching enlightenment.

Social tension and previous convention vs innovation, practicality and change

Gantumur speaks of the social tensions that arose when she made the decision to relocate the women’s hural from their small traditional Mongolian felt ger to the new building and its big temple. Despite highly vocal opposition, she went ahead with the big move and recounts how, a felt ger constructed by a Mongolian mind is great, but it is more suited to a nomadic lifestyle. When the anis and I sit in a ger for many hours doing puja, in the Winter time it is very inconvenient, getting so very cold from the back, and feeling so hot on our face from the front when we light the stove’s fire.

Championing and endorsement

The main sponsor of the present Tugsbayasgalant Temple building in Ulaanbaator is Mongolian Gelug Prelate Lobsang Tenzin Gyatso Pal Sangpo Guru Deva Rinpoche (1910-2009). In reference and sincere deference to his generosity:

No one lives only on her or his own power… from the time one is born from a mother, one becomes a ‘debt bag’ [12] … However one cannot repay a particular alms-giver, and so through developing a compassionate mind, purifying our soul and praying from our deep hearts, doing pujas, making retreats, reciting mantras, we can only hope that our debt gets smaller.

Role-modelling: mother (Mong. eej)

Gantumur considers her own mother as her most important role model, adding, generally a mother is like a Buddha. Mongolian poems praise thousands of abilities and qualities of a mother. For everybody, their mother is keeper of the highest Buddha nature.

Shavilah Arga: a Mongolian Gelug tradition

Gantumur is a product of a particular system of religious study in Mongolia referred to as shavilah arga. Here, one chooses one’s preferred Teacher and becomes their disciple and tries to learn from the Teacher without failure. Her chosen Teacher was Mongolian Guru Deva Rinpoche. Most of the anis at the women’s center have such a Teacher. They each go to their own Teacher to receive instruction. The other method of religious study in Mongolia is through classroom-based education.

Higher Education: Zanabazar Buddhist University of Mongolia

Given that, Mongolia had over 70 years established another system of study, [13] I would like my anis to receive a higher education in Mongolia. Gantumur Hambo proudly adds,

My anis, ‘were the first women to graduate from the Undur Gegeen Zanabazar Buddhist University of Mongolia (Shashnii Deed Surguuli in Ulaanbaator). Eleven Mongolian and 4 Buryat Mongol women, all together 15 anis graduated from the University on 27 June 2006 with a Bachelor’s Degree. The anis who graduated were all younger women.[14]

Tugs Hural : Operational considerations and livelihood

Tugs, the women’s hural, is a busy place which is open every day. The anis take one day off in turns. Gantumur and her anis receive a small nevertheless regular wage from the Center’s income. According to the Abbess, from the center’s monthly income in 2008, Tg 2,500,000 was spent on salaries. Each ani received Tg 100,000 per month. In 2008, there were 21 anis and 4 workers, all together 25 people. Most of the anis have taken their genen vow, so they can be married. However, most of the anis do not marry. Only two of the anis have taken their getsul vows. Three anis have children of their own, one of whom is now in her 40s and who first came to the hural eighteen years ago. Her child is now in the 4thgrade. She has never married.

In 2009 donations from devotees for ritual performances provided by trained anis are a major source of income for Tugs. Whilst this practice was already commonplace for lams all over Mongolia including UB-town, here I must emphasise that the fact that these Mongolian women-anis are being compensated/paid at all in exchange for ritual performances they are trained to perform was ground-breaking. Gantumur Hambo emphasised this point during our afternoon conversation. Who amongst us would not value a regular income stream however modest? It was administrator N.Gantumur who implemented this.

Where to from here? A reflection of her own Teacher (Mong. Bagsh) perhaps?

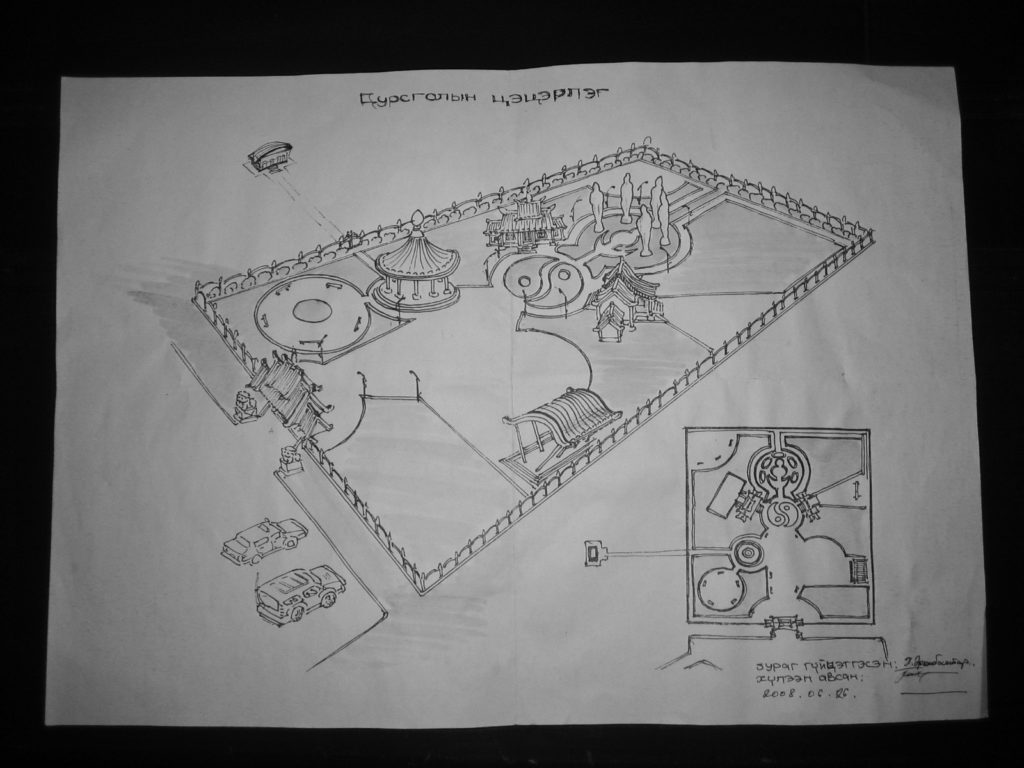

In the photograph of Abbess N.Gantumur at the beginning of this article, she is sitting at her desk with the preliminary sketches and plans for her next project. She was busy canvassing support for her next development project when my interpreter and I arrived.

Preliminary Line Drawings for a Tugsbaysgalant Meditation Park. Reproduced courtesy N Gantumur. 26 September 2008.

In 2008 Gantumur had set a new goal for the Tugsbaysgalant Women’s Center: that of purchasing land, hopefully on Bogd Mountain, and then developing it into a meditation park with a beautiful garden in memory of her Teacher Guru Deva Rinpoche. The land definitely needs to be somewhere on the outskirts of Ulaanbaator where city people can go to walk through and enjoy a beautiful garden out in the fresh air.

Her mentor, Mongolian Guru Deva Rinpoche had completed a similar re-development of urban land in 2006, albeit on a much grander scale (see below). His Zaisan Buddha Garden for the Mongolian people (in 2019 now increasingly being encroached upon by high-rise retail and residential development) has a giant statue of a standing Matreiya Buddha with a museum in the basement as its centerpiece.

The Zaisan Buddha Garden for everyone in Khan-Uul District, Ulaanbaator in the evening. 30 September 2008. Photograph: C Pleteshner

Gantumur’s own vision differs to that of her mentor in that the central statue, rather than being in the image of the future Buddha Matreiya, would be that of her own Teacher, ‘Guru Deva’. She adds, this garden park would be a proud expression of Mongolian ‘nationalism’, a prevalent discourse at the time. Five more statues are envisioned: Buddha, Bodh Zonghaba (Lama Tsongkhapa), Janraisig (Chenrezig) and Green Tara. There was still some indecision between whether the fifth statue should be of White Tara or Lovon Badamjunai.

Sponsors for all of these statues and for the purchase of the land would have to be found. Gantumur expressed concern, based on her own previous experience and also observation of the dealings of others, with only relying on one very wealthy sponsor for her park project. She felt that having only one rich sponsor would tempt them to take over and own the construction and then the precinct. Instead, she has (in 2008) decided to collect small amounts of money from many different kind-hearted people. In that way, the park would belong to all Mongolian people. In 2010, Gantumur Hambo and her Tugsbayasgalant Womens’ Center in Ulaanbaator celebrated their 20thAnniversary. She and Tugs anis are to be congratulated. For the benefit of others, not just oneself ...

Question: Reflecting on the application of the Trikaya Theory model of analysis outlined in Modes of Contribution, is Gantumur's contribution to revitalising her spiritual tradition in Mongolia physical, social of spiritual? What do you think? Does Gantumur's contribution differ to that of Tugs anis? If so how?

Now, like when watching a movie fast forward to July 2019 …

Ulaanbaator’s Tugsbaysgalant Gelug Women’s Centre continues to flourish. Mongolian women continue to come here for their own reasons: for pujas, for blessings, for guidance, for readings, for comfort, for support. They know where Tugs is located. They know how things work.

Let’s conclude the above discussion regarding contributions made by Mongolian womanhood to the revitalisation of their own spiritual traditions by reframing our consideration away from the intricate and specific details of ‘the local’ and consider Tugsbaysgalant Women’s Centre in the context of a broader globalising and digitally interactive social and virtual world.

As well-resourced (globalising?) pan-national streams of Gelug religious orthodoxies, led and driven by other imperatives and their english language establishments, continue to pour into the highly-contested local post-soviet socialist Mongolian Buddhist sphere and mediate its articulation for their various English language-reading audiences in other places, as far as we can ascertain, in Mongolia a Mongolian website ‘promoting, marketing or commercially branding’ Tugs religious services to Mongolian people in the most accessible written language for most Mongolians (Mongolian Cyrillic) has yet to appear. Maybe there is no need?

In terms of a Tugsbayasgalant Women’s Centre digital ‘online property and presence’, (such as you see here in CPinMongolia.com for example) as of yesterday (21 July 2019) there is still only a modest, straightforward and elegant Facebook account (see below) overseen by one of Tugs’ anis and maintained with her inner circle of Tugs supporters and friends. Here, you will find the dates of forthcoming Tugs pujas for women and others who may be interested in attending. It is all written in the local and most widely accessible language, Mongolian Cyrillic. Mongolian women in Mongolia know where Tugs is located. They know how things work.

Tugsbayasgalant Womens Centre Ulaanbaator. Active Facebook account screenshot. Accessed: 21 July 2019

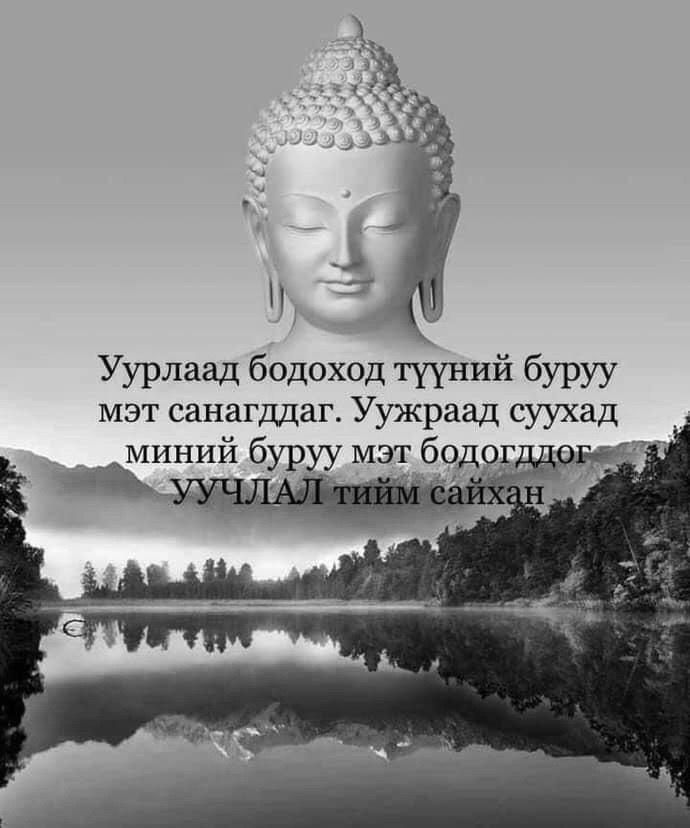

Other than dates and times of forthcoming pujas and events, the main other content to be posted on this Tugs Facebook account appears to be concise Teachings in the form of parables such as the one pictured below. In this instance, the topic for consideration is forgiveness.[15]

Digital screenshot of Tugsbayasgalant Women’s Centre allegory posting for their subscribers on Facebook. Image content unattributed. Accessed 21 July 2019.

Here concludes this vignette of Mongolian womanhood.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Ms. Temuulen Amarbaat for her assistance in preparing this article.

Further Reading

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: a social critique of the judement of taste (1979). Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Tsomo, Karma Lekshe ed. 2014. Eminent Buddhist Women, Excelsior Editions. Albany, New York: SUNY Press.

Footnotes

[1] Quote from Melbourne-based Australian playwright and novelist, Vanessa ‘Van’ Badham in The Guardian. Accessed: 29 May 2019.

[2] This vignette is based on a lengthy face-to-face interview held with N.Ganumur in 2008 and my own participant-observations in Mongolia since 2004.

[3] According to other women in the study, I understand that N.Gantumur’s husband was an Ynerpa at Gandantegchinlen Monastery (Mong. Гандантэгчинлэн хийд), an administrative manager-custodian responsible for the day-today running of the Monastery’s store houses in Ulaanbaator.

[4] In the context of my own ethnographic interests in Mongolia, Tugsbayasgalant Women’s Center in Ulaanbaator as a community of female practitioners is a related but peripheral node to that of my own investigation. More information about how Mongolian women living in the fast-growing metropolis of Ulaanbaator and their (changing?) engagement with Tugsbayasgalant Women’s Center and its anis would shed more light on the question of Mongolian womanhood and its (changing?) role in Mongolian Gelug Buddhist revitalisation in Mongolia. Curiosities associated with ‘similarities and differences’ of Tugs to the (male) monastic institutions and their religious specialist offerings to devotees could also be explored.

[5] Guru Deva Rinpoche entered Parinirvana in April 2009.

[6] Ш.Баясгалан (2008) has documented aspects of this formative development, particularly the relationship to Guru Deva Rinpoche.

[7] ‘Tugsbayasgalant’ can be translated ‘place of perfect happiness’.

[8] I can only assume that in 2019 her familial kinship network is now far greater in number than this.

[9] Throughout my qualitative research study, Mongolian women in Mongolia used the English word ‘soul’ when speaking about their Buddhist spirituality. This includes Mongolian people who are translating. From my linguistic perspective, ‘soul’ is a specific technical term, one that does not easily ‘map across’ to Buddhism and its logic such as ‘dependent arising’ etc. However, it is not my place to overwrite my study informants and translators’ preferred concept words, and so I have retained ‘soul’ although an inner discomfort regarding doing so persists. I do think the use and attributed meanings of a word such as ‘soul’ to Mongolian people in Mongolia deserves further scholarly investigation. Unfortunately, this particular area of linguistics and semantics is not my field.

[10] The implication here being, as well as men.

[11] Not allowing women to climb to the upper reaches of Otgon Tenger (Mong.Отгонтэнгэр) Mountain in Zavkhan Aimag in Mongolia may be an example of such tacit prohibition and socially-sanctioned dissuasion.

[12] ‘Debt bag’ is a Mongolian expression used to describe someone who has accumulated a lot of debts.

[13] A reference to increasingly Soviet socialist-monitored formal educational programs and their frameworks, emerging in 1920 and prevailing until 1990.

[14] Gantumur Hambo indicated that she does not encourage older anis to pursue formal, institutional study. She quotes a Mongolian proverb that loosely translates as, Learn at 60 years of age then die at 61. Older anis are instead encouraged to meditate rather than engage in more scholarly pursuits.

CP addendum: I found this very interesting, if not a little challenging given that investing time and money in higher education in various situs and locales is what my own ‘mature’ cohort of friends and I are still doing, women and men alike. In conversation we speak of Lifelong Learning. There are theoretical underpinnings (i.e. cognitivism, constructivism, Gestalt) but generally speaking our preoccupation, our ‘lifestyle’ if you like, is that of an ongoing, voluntary, structured and self-motivated pursuit of knowledge that is more often than not accompanied by some form of teaching and learning in its wake.

[15] ‘Forgiveness’ is a debated topic amongst North American Buddhists. For example, Ken McLeod argues that ‘forgiveness’ is where the dynamic in a relationship that once tied two parties together no longer holds. According to an alternative logic, however, such a shift is not the result of the dissolution of a ‘debt of honour’ and its inter-personal dynamic. Forgiveness is not ‘Buddhist.’ (See McLeod, K. 2017 Tricycle Magazine Feature (History and Philosophy) Accessed: 22 July 2019.

Author’s notes

This is an updated and revised vignette from a larger collection of written narratives about contemporary Mongolian women and aspects of the cultural and social worlds within which they are individually situated (Pleteshner, C. 2011. Nomadic Temple: Daughters of Tsongkhapa in Mongolia. Zava Damdin Sutra and Scripture Institute, Ulaanbaator. Unpublished manuscript). Each vignette is grounded in ethnographic fieldwork (2004- ) and interviews with the person about whom I write. All of the people in this assemblage are Khalkha Mongols, the largest group of ethnic Mongol peoples living in Mongolia today. I would like to thank Damdin Gerelbayasgalan for the considerable effort she put into formally transcribing recordings of interviews conducted with Mongol women across the country in 2008. Vignettes in the CPinMongolia.com series are grounded in these and other Mongolian women’s voices. Italicised text has been used to render their own words.

This article Vignette 07: Gantumur was researched and written by Catherine Pleteshner.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone using or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2024. CP in Mongolia. This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 22 July 2019. Last updated: 20 June 2022.