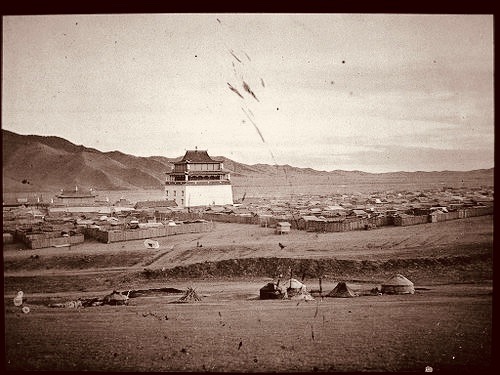

Baruun khüree or Gandantegchinlen Monastery in Urga now Ulaanbaator in 1913. Photograph by Stéphane Passet (1875-1942). Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gandantegchinlen_Monastery#/media/File:1913_in_Khuree.jpg

Following a relatively peaceful democratic revolution in 1990, a new Mongolian constitution was introduced on the 13th January 1992 establishing a parliamentary democracy in Mongolia, and so began another transition for people who make their home in Mongolia. A transition(al) economy is one which is changing for a centrally planned economy towards a free market (Feige 1994).

Post-socialist theorists such as Katherine Vedery (1996, pp15-16) however, express a fundamental disagreement with prevalent ‘assumptions in the literature’ at the time, instead arguing that ‘transition’ (for Baltic states) is incorrect in the assumption that a transition is occurring away from socialism to that of capitalism, democracy, or market economies. Rather, she argues that the 1990s were a time of transformation in post-socialist countries; ones that can produce a variety of forms, some of which approximate Western capitalism but others that do not.

View from the south-facing footsteps to Migjid Janraisegiig süm (Janraiseg datsan), Ulaanbaator Mongolia 21 August 2004. Photograph: C Pleteshner.

Nevertheless, the dramatic collapse of Mongolia’s economy in the early 1990s, as well as that of other eastern European countries, precipitated (or resulted in?) the reconsideration of ‘transition’ in purely economic terms. Transition can also refer to processes occurring [from] within the social and political life of communism, to that of a society, characterised by a liberalisation of the market and democracy in different aspects of the social and political life (Vasilenko 2006, cf. to Kornai 1990).

Convened by the Khalkha Mongol Buddhist prelate Zava Damdin (1976- ), international guest speakers and research academics at the Zava Damdin 140th Anniversary Conference at The National Library of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar. 2 Sept 2007. Photo: C.Pleteshner.

The neo-political approach of transition theory initiated the specific interest in different social spheres of transition. Scholars, at that time, began to shift their attention from the economic aspect of transition (Sharma 1997) to the cultural aspects (Hedlund 1999) whereby the historical roots of a heritage identity (See: Motif 03: Dragons Dancing with Blue Wind) can play a crucial role for outcomes in the restructuring of a transitional society (Deery 1995).

Designed by the Khalkha Mongol Buddhist prelate Zava Damdin (1976- ) the construction of the third temple at Delgeruun Choira begins. Dundgovi Aimag in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. 27 August 2008. Photograph: C.Pleteshner

And then, for the first time, social and cultural deliberations were considered in the transition theory formulations.[1] Tacit acknowledgement of a cultural approach to transitional processes, if only from the perspective of the actors, is also an important consideration. Not new to the theoretical and methodological discourse, it continues to be somewhat problematic to substantiate.[2]

An audience of many thousands attended at the Gandan Lhagvaa Puja conducted by the Khalkha Mongol prelate Zava Damdin (1976- ) at the Buyant Ukhaa Sports Palace (Mong. Буянт-Ухаа Спорт Цогцолбор) in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. 4 March 2017. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

Соёнбот Oрон (Eng. Soyombot Oron) Opening Celebrations led by by the Khalkha Mongol Buddhist prelate Zava Damdin (1976- ). Delgertsoght Sum in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. 15 August 2017. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

Delgeruun Choira in the Gobi Desert Mongolia. Соёнбот Oрон (Soyombot Oron) opening ceremony concert convened by the Khalkha Mongol Buddhist prelate Zava Damdin (1976- ). 15 August 2017. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

Khalkha Mongol Buddhist prelate Zava Damdin (1976- ) Оточ Манла (Eng. Otoch Manla) Initiation at the Ulanbaator Palace in Mongolia. 17 February 2024. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

If we accept that ‘transition’ in an economic sector such as ‘religion’, and the organisational ‘nodes’ that support its operation cannot take place without changes in the social institutions including the kinship groups with which they engage, then evidence of the emerging social and organisational forms that transition reform in religion is taking place in Mongolia offers us new possibilities when considering changing national ideas, as well as social ideals. The significance of this theoretical approach is far-reaching.

The connection to my own research interests (that of a socio-cultural sphere in transition) is clear: Mongolian Gelug Buddhism in Mongolia, if only in the one extended community within which I am ethnographically-situated, is a social sphere, a cultural sphere as well as a religious sphere. Here, there continues to be an attraction to, and generation of considerable personal investment in an explicitly stated and demonstrated [re]construction and revitalisation of some kind[s] of cultural heritage identity. This is what I see when looking at the above series of photographs. What comes to your mind, when you look at these photographs?

For my own longitudinal study (2004-2024), I have been a participant-observer in the progressive emergence of a now visible and multi-nodal infrastructure and a range of integrated personal and group-based Buddhist practice ‘modalities’ in Mongolia. A growing number of inter-generational kinship groups, the huurai kin are becoming and staying involved. So what’s going on here?

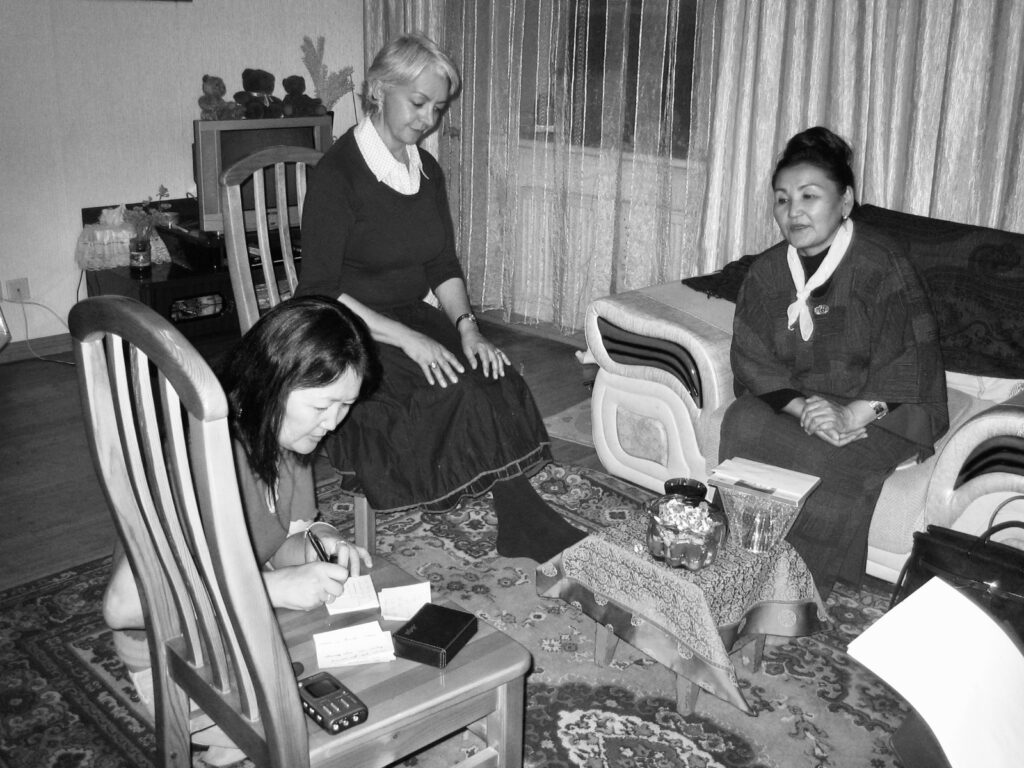

Mongolian Womanhood Project, Urantsetseg interview in progress. Research Assistant Damdin Gerlee (left), CP (centre) and Urantsetseg (right). Ulaanbaatar, 24 September 2008. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

Notes

[1] See Vasilenko (2006, pp83-89) for a summary of the ‘social implications and political dimensions of transformation’ discourse from the 1980s until 2006.

[2] A useful discussion of the complexities associated with assumptions associated with studying ‘transition’ in transitional societies some of which include difficulties in acknowledging a cultural approach within transitional processes can also be found in Valisenko (2006, pp90-96).

References

This article is an updated extract from Pleteshner, C. (2011). Nomadic Temple: Daughters of Tsongkhapa in Mongolia (Unpublished manuscript, The Zava Damdin Sutra and Scripture Institute Library Archive in the Manjushri Temple of Delgeruun Choira. Appendix C, pp335-6.)

Deery, P. 1995. “Handcuffed to History: Russia and the Politics of Memory.” Quadrant (April): 67-71.

Feige, Edgar L. 1994. “The Transition to a Market Economy in Russia: Property Rights, Mass Privatization and Stabilization.” In A Fourth way?: privatization, property, and the emergence of new market economics, edited by Gregory S Alexander and Grażyna Skąpska, pp57-78. New York: Routledge.

Hedlund, S. 1999. Russia’s ‘Market’ Economy: A Bad Case of Predatory Capitalism. London: UCL Press, Tailor and Francis Group.

Sharma, S, ed. 1997. Restructuring Eastern Europe: The Macroeconomic of the Transition Process. Zagreb: University of Zagreb.

Vasilenko, Irina. 2006. “Educational Transformation in Transitional China and Russia: a comparative analysis of private schooling in Beijing and Moscow.” PhD, School of Social Sciences, Victoria University.

Verdery, Katherine. 1996. What Was Socialism, and What Comes Next? Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [Princeton Studies in Culture/Power/History. Edited by Sherry B Ortner, Nicholas B Dirk and Geoff Eley].

Further Reading

In terms of additional context, the following articles by Li Narangoa (Professor, School of Culture, History & Language, Australian National University) are well worth reading:

- Narangoa, L. (2009), Mongolia and Preventative Diplomacy in Asian Survey. 49, 2, p. 358-379. Abstract: Since 1992, Mongolia has sought to embed itself and its neighbors, Russia and China, in regional security arrangements and international law. This strategy can be categorized as preventive diplomacy and involves seeking to create a climate in which conflict will not arise, rather than managing conflict after it has emerged. To access the document: http://hdl.handle.net/1885/39011.

- Narangoa, L. (2023). Mongolia in 2022: From the COVID-19 Lockdown to Opening the Border. Asian Survey, 63(2), 336-346. Abstract: As in 2020, the biggest stories in Mongolia in 2021 and 2022 were elections, COVID-19, and how to cope with the contracting economy. At the end of the year, Mongolia was struggling to meet public health challenges and to recover from the economic downturn. Both the government that was elected in 2020 and the president who took office in 2021 have promised to improve corruption, which is endemic in Mongolia, but people have yet to see much change. Popular dissatisfaction led to a huge public protest in December 2022 that demanded the government ensure more transparency in the coal trade. Thirty years after a peaceful transition to democracy, Mongolia is facing its greatest challenge: how to maintain and develop a transparent democracy that truly cares about public opinion and people’s livelihoods.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone using or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2025. CP in Mongolia. This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 14 March 2024. Last updated: 15 March 2024.