Photographs taken in Mongolia are courtesy of Temuulen Amarbaat

‘Gaden Lhavjaa’ (Tib. Gaden Lha Gyai-ma) is a liturgy and representational image that supports visualisation, devotional prayers and other yogic practices in honour of the Gelug lineage’s scholar-spiritual master Je Tsong Khapa (1357-1419), also known by his ordained name Losang Drakpa (Wylie: blo bzang grags pa) or more simply as ‘Je Rinpoche.’ Source: Front cover of a booklet prepared by CP for an Australian meditation group practice in honor of TP Adele Cima’s lifelong commitment to the Gelug lineage and its Teachers. (Artist: unknown) Melbourne, 7 September 2010.

Je Tsongkhapa

In terms of articulating a coherent matrix of philosophical reasoning (with its own ontology, epistemology, ethics and internal logic) Je Tsong-khapa [i] wrote two main treatises: the Lamrim Chenmo (see Cutler and Newland 2000, 2004, 2002, Gonsar Tulku Rinpoche 2010) [ii] and Ngakrim Chenmo (Wylie: sngags rim chen mo). His activities and analyses resulted in the formation of the Gelug lineage of Buddhist philosophical reasoning.

Mongolian Gelug torma offering, with a meticulously stacked base of traditional bread decorated with hand-made dried yogurts (commonly used at this wintery time of the year). On top of this is placed the ornate torma offering made by one of Zava Damdin’s senior lineage lams. A ‘thangka’ (Tib.: ཐང་ཀ་)—a representational hand painting on cotton surrounded by Indian and Nepalese silk brocade appliqué is depicting Je Tsongkhapa (centre-top) and his immediate descendent lineage students below. This elaborate installation is positioned on the stage next to Zava Damdin’s right hand. Gandan Lhavjaa Puja, Ulaanbaator Mongolia 4 March 2017.

Gandan Lhavjaa Puja in Ulaanbaatar

On the afternoon of Saturday 4 March 2017 Zava Damdin (1976– ) led the Gandan Lhavjaa (Tib. Gaden Lha Gyai-ma) puja. On this occasion, the local-to-Mongolia Gelug adaption was (i) Gandan Lhavjaa followed by (ii) Janlav Tsogzal. The event was organised by Dugarjav (Lobsang) Bilguun with the assistance of family and friends, and was held at the Buyant Ukhaa Sports Palace (Mong. Буянт-Ухаа Спорт Цогцолбор) in Ulaanbaatar.

Differentiation Markers

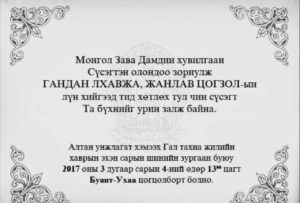

One of the ‘differentiation markers’ associated with such events and ritual performances by Zava Damdin’s Gelug lineage in Mongolia is that attendance is by written invitation (see below).

Official invitation issued by Dugarjav (Lobsang) Bilguun to attend the Gandan Lhavjaa ritual performance. 4 March 2017.

Another marker of differentiation is that attendance at ritual performances is also free of charge. My own observations have been that since 2004, when the considerable reconstruction of infrastructure effort at Delgeruun Choira began, Zava Damdin and his mother Jatsan Gundegmaa have insisted that attending pujas or dharma teachings should continue to be free of charge. This is certainly not the case with Gelug institutions and organisations in Australia (for example) where as a minimum a ‘facility fee’ is usually charged.

Indeed, the hosting ‘on costs’ of such events in Mongolia are considerable with the ‘rebuilding of infrastructure’ costs being greater still. To this end, attendees wishing to participate in the ‘reconstruction’ of Delgeruun Choira effort can do so through donation (see below) although many express their support through other means. For example, these donation boxes themselves are a donation from a prospering Mongolian manufacturing firm, the family-owners of which are local supporters of Zava Damdin and his vision.

The third differentiation marker I would like to bring to your attention is the innovative use and inclusion of information and communication technologies (ICTs) as a virtual-visual staging modality digitally projected during the actual puja performance in ‘real time’ (cf. as it is happening).

Zava Damdin leading the Gandan Lhavjaa Puja (Tib. Gaden Lha Gyai-ma) at the Buyant Ukhaa Sports Palace (Mong. Буянт-Ухаа Спорт Цогцолбор) in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. 4 March 2017.

The above photograph shows how the faces and physical forms of the ‘lams’ (Mong. for monks) in the front row as well as those of the audience seated behind are reflected back and thereby made public—each to the other.

Although commonplace in elite performer-centred musical and theatrical contexts, the presence of the required high end ICTs is here noted, in terms of a presentation modality, I have never seen this before at a Gelug puja—anywhere. Usually such camera work-monitoring is focussed on what is happening centre stage and only occasionally pans out into the audience to bridge the separation of the on-stage performer/s—audience effect. Yet, how often have I sat behind such a row of lams asking myself, ‘Are you chanting? What are you chanting? Are you doing mudras? What are you doing? What’s going on?’ This innovation brings with it a variety of considerations which can be better addressed in a separate article. To continue …

An audience of many thousands attended the Gandan Lhagvaa Puja (Tib. Gaden Lha Gyai-ma) conducted by the Mongol Gelug prelate Zava Damdin (1976- ) at the Buyant Ukhaa Sports Palace (Mong. Буянт-Ухаа Спорт Цогцолбор) in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia on 4 March 2017.

Of course, across the whole group, phenotypic expressions and appropriate external behaviours were maintained by the differing social and performative roles considered correct for such an event. Little is revealed in terms of participants’ core motivations or emotions.[iii] Such personal ‘containment’ is highly visible in the Mongolian social circles I frequent. My experience is that this particular marker of (a contemporary and cosmopolitan Mongol?) identity at such events in Mongolia, is not only visible but quite stable across generations within the community who attend. I guess its proscribed behaviour. Seems reasonable don’t you think?

Porous Boundaries

However, once the formalities of such a ritual performance by Zava Damdin are concluded, and oftentime even before, as the following picture shows, visually and socio-spatially, the boundary between Mongol lams and secular-devotees is challenged by secular participants therefore becoming porous.

Whilst the venues may be more elaborate, and now have individual chair-seating for the (secular) participants—whilst before we all sat, and were comfortable sitting, with the lams on the floor—the propensity for some (secular) practitioners to express their connection and other personal ideation physically through prostration, has been present since I started doing fieldwork and attending such ritual ceremonies in Mongolia back in 2004.

It seems that we in the ‘Anglo-sphere’ West may be far more contained (less spontaneous or more conservative?) in this regard. Here, I stop short of considering whether this is a good thing or not. Suffice to stay, I am deeply touched by these personal and very public acts (purposeful, spontaneous, whatever) whether they are being performed out of humility or not.

Mongolian secular devotees (women, men, old, young, children) in Mongolia (spontaneously?) doing repeated full body prostrations in front of Zava Damdin and whilst Mongol Gelug lams (seated) look on. The Gandan Lhagvaa Puja (Tib. Gaden Lha Gyai-ma) conducted by Zava Damdin at the Buyant Ukhaa Sports Palace (Mong. Буянт-Ухаа Спорт Цогцолбор) in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. 4 March 2017.

One final observation. At the heart of this emerging lineage of Mongol Gelug Buddhism in Mongolia, as part of their training, lams are expected to develop highly competent organisational and communication skills. For as long as I’ve been involved, it has not been considered adequate to just sit on one’s meditation cushion reciting mantras and studying texts. In terms of porous role boundaries, in this Mongol Gelug pond everyone multi-tasks!

Dugarjav (Lobsang) Bilguun, organiser of the Gandan Lhavjaa Puja (Tib. Gaden Lha Gyai-ma) at the Buyant Ukhaa Sport Palace. Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia 4 March 2017

References

Cutler, Joshua W. C. , and Guy Newland, eds. 2000. The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment by Tsong-kha-pa (1357-1419). Edited by Joshua W. C. Cutler 1ed. 3 vols. Vol. 1. Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publications.

Cutler, Joshua W. C. , and Guy Newland, eds. 2002. The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment by Tsong-kha-pa. 1 ed. 3 vols. Vol. 3. Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publications.

Cutler, Joshua W. C. , and Guy Newland, eds. 2004. The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment by Tsong-kha-pa. 1 ed. 3 vols. Vol. 2. Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publications.

Gonsar Tulku Rinpoche. 2010. CP (unpublished) transcript of Commentary on The Great Lam Rim Chen Mo by His Eminence Jetsuen Tendzin Kaedrup Jigme Namgyael Gonsar Tulku Rinpoche. 10th Annual Lam Rim Retreat (14 May – 13 June 2010). Rabten Choeling Institute for Higher Tibetan Studies, Le Mont Pelerin, Switzerland. 655pp.

Kraschewsky, Rudolph. 1967. Das Leben des lamaistischen heiligen Tsongkhapa Blo-bzan-grags-pa (1357-1419) Dargestellt und erlautert anharnd seiner Biographie Quellort allen Gluckes. Bonn.

Thakchoe, Sonam. 2003. “‘The relationship between the two truths’: a comparative analysis of two Tibetan accounts.” Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal 4 (2):111 – 127.

Thakchoe, Sonam. 2005. “Transcendental knowledge in Tibetan Mādhyamika Epistemology.” Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal 6 (2):131 – 152.

Thakchoe, Sonam. 2007a. “Status of Conventional Truth in Tsong khapa’s Mādhyamika Philosophy.” Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal 8 (1):31 – 47.

Thakchoe, Sonam. 2007b. The Two Truths Debate: Tsongkhapa and Gorampa on the Middle Way. Boston: Wisdom Publication.

Thakchoe, Sonam. 2008. “Gorampa on the Objects of Negation: Arguments for Negating Conventional Truths.” Contemporary Buddhism: An Interdisciplinary Journal 9 (2):265 – 280.

Footnotes

[i] Refer to Rudolph Kraschewsky (1967).

[ii] Sonam Thakchoe (University of Tasmania, Australia) whose research interests are in Indo-Tibetan philosophy with a particular focus on Madhyamika ‘Middle Way’, has tackled analysing the ‘Two Truths’ debate within Madhyamika philosophical reasoning; that of the Gelug’s School Je Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) and the other of the Sakya School’s Gorampa Sonam Senge (1429-1489). See Thakchoe 2007b, 2003, 2005, 2007a, 2008.

Note: Whilst I make no claim to fully comprehending the nuances underpinning these differing trajectories of philosophical reasoning, I do however continue to read such critical and analytical scholarly considerations in order to cultivate my own small mind. These readings are at the boundaries of what I have been taught and therefore on topics, although relevant, with which I am less familiar.

[iii] See J.Hall, L Grindstaff & M.C. Lo (Eds.) 2010. Handbook of Cultural Sociology p225.

[iv] See M Micklin & D L Poston Jr (Eds.) 1990. Continuities in Sociological Human Ecology p176.

end of transcript.

The post Out and About 04: Gandan Lhavjaa in Ulaanbaatar was written by Catherine Pleteshner.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating the photographs or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2025. CP in Mongolia. This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 5 March 2017. Last updated: 20 June 2022.