Mongolian Womanhood Project,”Urantsetseg” in Ulaanbaatar, 24 September 2008. Photo: C.Pleteshner. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

Urantsetseg is such a charismatic person. Even before you engage with her in conversation, you cannot help but be struck by her serene countenance and grace. Stylish in both dress and coiffure, Urantsetseg’s social comportment is impeccable. The manner in which she engages with others is ever-mindful and considered; her use of language, purposeful and precise.

Urantsetseg was born in Tsetserleg Sum in Arkangai Aimag. The eldest of five children, she completed her junior schooling as well as her higher education in Ulaanbaator.

After graduating from the Faculty of Mongolian Language and Literature at the State Pedagogical University in 1977, she started her professional life as a press worker for the State Press Committee. For ten years she was the Assistant Editor of the Mongolian Government’s children’s newspaper, The Truth of Pioneer. In 1990 she was promoted to her next position, that of Assistant Editor of the newspaper Teacher, the official press for Mongolia’s Minister of Education and Training. After another seven years as Executive Director for the newspaper Ulaanbaatar, the Central Press of the nation’s capital, Urantsetseg took up the position of Vice President of the news agency for Mon Tsa Me, Mongolia’s Electronic News.

As I listen attentively to her words, I cannot help but be impressed. It soon becomes apparent, that like many other Mongolian women in our social sphere, Urantsetseg has seldom, if ever, been asked to give such a summarised account of her own working life. So naturalised are the personal habits of this generation of Mongolian women, that they embrace the many and varied jobs of responsibility they have been given and simply get on with their work.

Another of Urantsetseg’s most recent contributions (2006-8) to contemporary Mongolia’s printed and published legacy , however, is through her considerable editorial involvement in the revisioning (of Mongolian history) in the two volume Mongolian Encyclopedia published by The Mongolian Academy of Science.[1]

This is only the second time that such an authoritative, officially-endorsed national ‘Encyclopedic’ of cultural history has been completed. Written in Mongolian Cyrillic, it is valued by many in Mongolia’s literati circles as an important reference text for Mongolian high school children and all Mongolians! This latter compendium is much expanded.

In terms of her own family life, Urantsetseg is married, has three children; one son and two daughters. She now also has grand-children. In addition to these considerable family responsibilities, she also manages to find the time to provide senior editorial support for Zava Damdin Lama’s first book, ‘The Yellow Book’ published in 2007 to coincide with the 140th Anniversary of Zava Damdin Lama Conference and other celebrations in Ulaanbaator.

Although she considers that linguistically and semantically, the final publication had no mistakes, the meaning of the actual text was written at such a high philosophical level of knowledge that it was far beyond her understanding, leaving her unsatisfied with her work.

She recounts how she persevered with the task but was nonetheless frustrated by not understanding the meaning of the book with which she had worked so closely. And so, in order to get closer to that particular area of study (Mongolian Buddhist philosophy in the tradition of Je Tsongkhapa), she has now developed the habit of reading all the information available on the topics discussed. Urantsetseg’s approach is consistent with that of other Mongolian women I know: obstacles are just challenges for which solutions need to be found!

Urantsetseg has also contributed to the production of two other books about Mongolian Buddhism, assisting Hor Choinjun Zavaa reworking the original publications into the modern Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet thereby making them more accessible to Mongolian people who may be interested. Given her considerable editorial contribution, Urantsetseg is incredibly modest. To quote, I cannot say I helped, even the word ‘help’ and ‘assistance’ seem too high for me in this matter.’ In her hands seemingly self-effacing words simply dissolve into a constant and genuine humility.

In 2013 she prepared the Mongolian texts for the multi-lingual Echo of the Snow Land. The publication was rendered from the original Tibetan composition in poetic form into both the traditional vertical and Cyrillic Mongolian scripts as well as being translated into the English language. For those who may be interested, the full citation for this artistic and scholarly publication about the history of Mongolian Buddhism (from an authentic Mongolian Buddhist scholar’s perspective) is as follows: Zavaa Damdin Rinpoche Lobsang Darjaa. 2013. Echo of the Snow Land (a distributed formal address in the form of a booklet including original artworks of the author to all participating delegates of the Thirteenth Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies IATS in Ulaanbaatar 21-27 July 2013). Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: Zava Damdin Scripture and Sutra Institute, Delgertsogt Mountain Mongolia. When one keeps the company of serious Mongolian scholars, then there will always by important editorial work to be done.

In Urantsetseg’s family, on both parents’ sides there were lams. (The honorific ‘lam’ not the westernised Tibetan ‘lama’ is used by Mongolian people to refer to their Buddhist clergy.) She continues, we were and we have continued to be a very religious family. My great uncle was a Dooromba in Rashaat Monastery in Arkhangai Aimag where the biggest counter-revolutionary uprisings took place! A lam from my mother’s side, he did not marry. Nor did he have any children. He was executed when he was 37 years old.

And so, Urantsetseg was the one who handled his exoneration and compensation negotiations with the Mongolian Government. Now, as a reminder, she keeps those official papers in his honour on her family’s altar of which she is custodian.

According to her Bagshaa, a lam’s rank depends on the way one did the retreats to achieve a certain level of study. One who accomplished a retreat sitting on a rock was called ‘Dooromba’. Urantsetseg was born and grew up in the countryside. Gimbi Bantihai, Urantsetseg’s grandfather’s brother, who lived until she was in the 4th or 5th grade, was the only surviving lam in her homeland. It was he who directed and taught her and the others in her extended family religious practices in a hidden way.

Urantsetseg still has just a few material things from this lam in her household: a tsatsal (a device used for ritual sprinkling), and some beads from a very old mala. They are such precious things, for they tell a story for which mere words cannot account. She keeps these close to her heart, on the altar.

For as long as she can remember, she has made a tea offering every morning and a handmade butter lamp offering every evening. She recounts how, when she was young, religious items were never visible or displayed at home. Instead, a simple book holder was used by the family as an altar. So it was here that the traditional daily black tea offering continued to, uninterrupted, be made.

Urantsetseg’s husband is one of seven children. Once again, families of this size were the norm rather than the exception during the socialist era. Both Urantsetseg and her husband are the eldest children in their respective families. Her father-in-law is a trained artist, so too is her husband. He is also religious, with many lams on his side.

She feels that because they have this similar background, they do not have any living or custom differences, or conflicts that could arise from such differences. Is there a suggestion embedded here that points toward such conflicts arising in couples who are not so well-aligned? Is this why some Mongolians still prefer to keep like-minded company with their own?

In conversation, Urantsetseg’s many stories of traditional rituals and her own childhood flow easily from one to the next:

Another interesting memory relates to the ‘religious ritual’ (her term) ‘shireg’ for a baby, when she/he cries. Mongolians used to live in gers where everybody lived together. When a visitor came in, an infant cried more so than in their usual way… it seems that infants feel greatly the negative energies of others.

For a Mongolian woman, the way to stop an infant crying and to cure this was a ritual called ‘shireg’. A handful of soil is taken from the entrance area, the place on which a stranger has stood, and put in water. A small amount of melted hot aluminum is then poured into cold water mixed with some soil. Doing so makes a loud sound. We then hold the baby over it and circle around saying phrases like:

Shireg shireg shireg tajig suha [mantra].

Ailiin hunees bolov uu/ Are you afraid of the neighbour?

Ayanchin giichingees bolov uu/ Did you become afraid of a visitor?

Buh murguh gee yu/ If a bull has threatened you

Buur hazah gee yu /(or) If a male camel has been tempted to bite you

[There are many words one could say here ]

Chi yunaas aiv /What is it that frightened you?

After circling your baby over the water several times, you take the aluminum out of the water and study the shape of it to diagnose what caused the baby to become frightened. The ‘Shireg’ action is repeated three times until that certain shape disappears. The baby would then stop crying and gently fall into a calm sleep.

According to Urantsetseg, there are a variety of ways that Mongolian women perform the shireg ritual. These vary in both context (private and public) as well as in terms of place. Although intended to ameliorate the same problem, there is considerable variation in the performance of a shireg from one region to the next. Urantsetseg goes on to describe a range of simple everyday shireg as well as others for important occasions.

Consideration of the wellbeing of others is never far from Urantsetseg’s evocative narrations. Urantsetseg’s memory of her own childhood experiences is very strong. Her homeland is the place where Zaya Gegeen was born, the place called Muhar Hujirt. Her whole family, together, goes on pilgrimage there every year to drink the mineral water and to pay homage to its grand mountains and ovoo.

Over the years, Urantsetseg has taken the time to recount to me, patiently and in detail, many fascinating stories of how she managed to sustain continuity in her traditions and spiritual inheritance, right through the socialist times:

When I was young I worked in the Central Committee of the Mongolian Youth, and I organized hidden visits for the workers to Ganden Monastery during Tsagaan Sar. It was a time when all religious practices were prohibited, but [nonetheless] everybody still felt the need.

For Urantsetseg, this is a testimony to her devotion and courage:

During the ten years I worked for the Central Committee of the Youth, from 1980 to 1990, I felt different from others in terms of religious practices and belief. Colleagues teased me that if the time was right I, at least would have been a wife of a Maaramba. [a gentle smile]

During the socialist times we would invite lams secretly, to get pujas done at home. Celebrating Tsagaan Sar was prohibited in the city and town, saying it is a celebration only for herdsmen. So it was very difficult to visit Ganden monastery. But we did it in the morning of Tsagaan Sar, divided in groups of three and taking turns, even though we had to register our working time. My uncle’s family, the household to which I was taken to be cured of my cough, had to move away from the center of their little town out into the remote countryside. Here they would remain hidden from other people.

And what of the role of traditional practices in contemporary Mongolian life?

Even though I am a relatively intelligent person, I am actually also very religious. I would say that my spiritual lineage is making me how I should be as a Mongolian woman, as the person I am. If I were to go in a different direction, I would lose the meaning of my existence.

To the North of our Summer house there is a beautiful mountain. Last Summer, when it was a full moon, we happened to walk outside. Then one of my grandchildren asked me if we could recite maani [cf. mantra] sitting around there all together, outside. To me, this means there is something in their hearts. To feel the full moon and beautiful mountain and relate it to a religious practice such as reciting maani. What better can possibly be done?

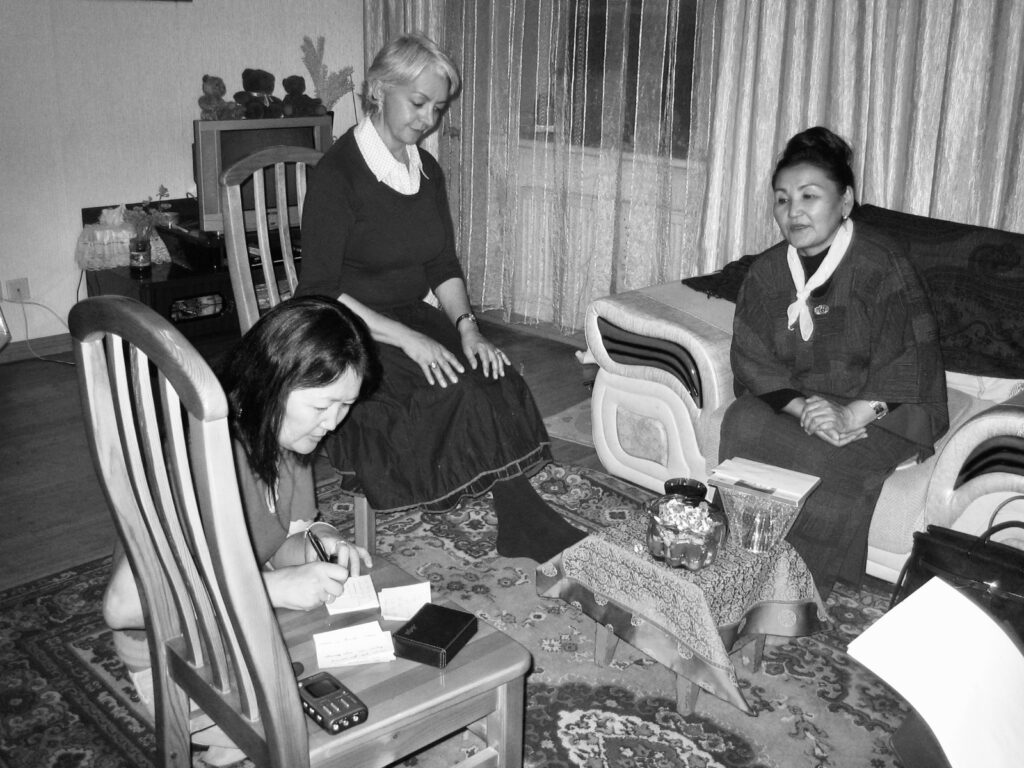

Mongolian Womanhood Project,”Urantsetseg” interview in progress. Research Assistant Damdin Gerlee (left), CP (centre) and Urantsetseg (right). Ulaanbaatar, 24 September 2008. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

And finally, what of other people’s engagement with Urantsetseg? Over the years I have had many opportunities to observe Urantsetseg working with others in our social circles in Mongolia. I cannot help but be drawn to speculate on the extent to which, how very close Urantsetseg comes to embodying commonly-held notions of idealized womanhood for many of the Mongolian people in our social spheres. She is intellectually alert and culturally knowledgeable. She is gracious, capable and kind, her presentation impeccable and her countenance serene. Like Yanjinmaa and Tara inhabiting their own psycho-social worlds in a scroll painting, instead they are here in our midst.

Somewhat old-fashioned I hear you say? Well, not really. Surely, seamlessly traversing the political editor’s journey from socialist through post-socialist endeavours has not been, after all, such an easy ride. To the contrary, Urantsetseg continues her life-long journey now alongside like-minded others. She continues to materialise together with these others, a growing collection of complex, important and substantive educational (for the broader Mongolian public) works.

[1] The full citation in Mongolian Cyrillic is: МОНГОЛЫН НЭВТЭРХИЙ ТОЛЬ (2000). Монгол Улсын Шинжлех Ухааны Академи Улаанбаатар.

Author’s note: This vignette is a revision of an earlier draft. This is one story from a larger collection of written narratives about contemporary Mongolian women and aspects of the cultural and social worlds within which they are individually situated. (Pleteshner, C. 2011. Nomadic Temple: Daughters of Tsongkhapa in Mongolia. Zava Damdin Sutra and Scripture Institute, Ulaanbaator. Unpublished manuscript). Each vignette is grounded in ethnographic fieldwork and interviews with the person about whom I write. All of the people in this assemblage are Khalkha Mongols, the largest group of ethnic Mongol peoples living in Mongolia today. I would like to thank D. Gerelbayasgalan for the considerable effort she put into formally transcribing recordings of some interviews conducted with Mongol women across the country in 2008. Vignettes in the CPinMongolia.com series are grounded in these and other Mongolian women’s voices. Italicised text has been used to render their own words.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating the photographs or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2025. CP in Mongolia. This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 15 January 2014. Last updated: 13 March 2024.