Contemporary Mongolian Womanhood Project: “Handmaa”. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission. 8 March 2024.

The lay of the land: anthropology-in-the-field

This vignette is an example of a particular modality of research-based story telling. “Handmaa” is not a fictional character but rather a person who I have come to know over many years, not only through conducting a one-time, out-in-the-field interview in 2008, but also through sharing life experiences in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert since 2004.

Whenever one is dealing with real people and their account of events, it is important to skilfully and respectfully manage (in one’s own retelling) such matters. As always, I endeavour to do so here.

Handmaa, this interviewee’s pseudonym, has been interpreted from the Mongolian as Goddess Mother. This attributed name was selected for her by other Mongolian women in the study who were contributing their own stories to my exploration of Mongolian-in-Mongolia women’s lives. See: Vignette 06: What’s in a Name? (2017).

In terms of appreciating this attribution in terms of its Mongolian culturo-buddhist context, Zava Damdin (1976-) adds that, ‘Handmaa’ is the Mongolian term for the Skt. ‘Dakini’ and the Tib. ‘mKha-‘gro-ma’. From ancient times, the Sanskrit term ‘Dakini’ has been used by Mongolian people. [Source: personal correspondence 10 March 2024].

Here, in ethnographic research terms, I am doing the participant-observation narration. I still remind myself on a regular basis, that it is these Mongolian women, the women and their huurai kinship network, who are doing the real work of embodying and revitalising their local spiritual traditions after the withdrawal of soviet socialist governance from Mongolia in 1990.

Two decades have now passed since I embarked on this project and I am still a scribe who shapes their stories in order to tell my own. I carry their voices with me as I continue to write articles for this blog, migrating away from their local, across and into this cultural, linguistic and digital relocation.

Handmaa’s vignette is composed in the present tense in order for it to serve as a historical record, a snapshot in time of what was happening and of interest and concern in 2008. From here, her own words and those of other Mongolian women have been rendered in italicised text. In their own culturally, proximally and linguistically-embedded terms, the pseudonym assigned by the other Mongolian women in the study communicates more about Handmaa’s qualities for them than I will ever be able to articulate in the English language, not only for myself, but for you.

__________________________________

HANDMAA

At pujas, one could quite easily miss seeing Handmaa. She does not wear clothes that draw attention to her presence; no richly woven and embossed deels or other attention-seeking vestments for her. Instead, she (almost always) puts on her favourite cultured pearls for such important occasions; just a single string of small blue-back pearls, to adorn her favourite Mongolian light blue-sky coloured vestments.

She dresses formally yet lightly. Why? Because before, during and after such ritual gatherings at Delgeruun Choira in Delgertsoght Sum in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, where crowds of many hundreds of people gather, Handmaa will be working the whole time, steadily along with other women in the extended family, the huurai kin. Like an intricate orchestral arrangement, nothing is said, yet all goes well.

Together, they will be watching, lifting, serving, carrying, chopping, guarding, folding, greeting, cooking, accepting, giving, explaining, directing and escorting. Ever vigilant of the goings on in and around the crowded ger-temple and its surrounds, it is their collective responsibility and shared goal to ensure that everything runs smoothly for all of their guests – so so many on this particular day. In the harmonious counterpoint to this orchestration, the Lamas and lams are visually centre-stage. It is they who perform the liturgies and incantations on the day, and sometimes days, of the event.

_________________________________

USSR Petigorsk newspaper article (1973).” Children from Different Nations’. Handmaa (centre, back row). Newspaper clipping courtesy of J.Avrazed. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

Handmaa, a trained and highly-skilled pharmacist, herself one of six children and now mother of two daughters, went to university in the city of Petigorsk. She was born in 1951 in Bayan-Ovoo sum[1] in Mongolia’s South Gobi Aimag. As a sign of friendship with the Soviet Union, Mongolian students such as Handmaa, along with students from many different other nations, studied in Russia. The above figure shows Handmaa (back row, center-left). Everyone in this publicity shot printed in the Soviet newspaper is female. Four other students are also from Mongolia; one of whom has become Handmaa’s trusted and life-long friend. They not only work together, they care for one another just as all heart-friends do.

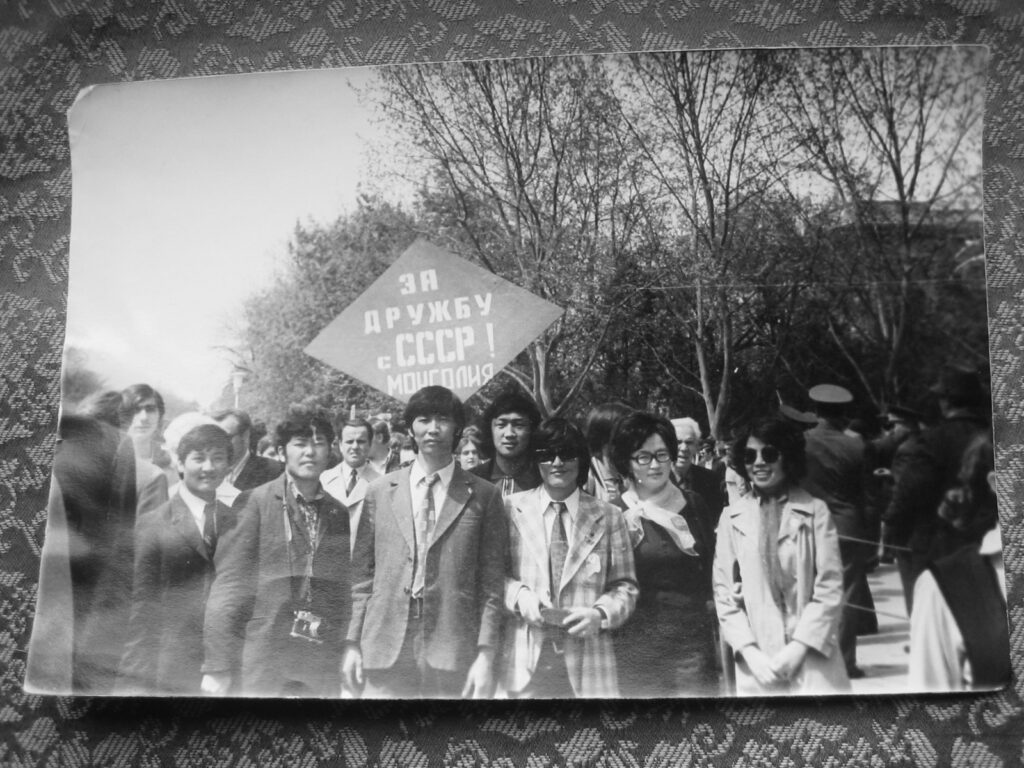

The nationalities of the others in this photograph are variously described by the Russian journalist as Armenian, Vietnamese, Russian, Ossetian, a Kenyan and a Tatar-ka (from Tartarstan). We not only studied together but also celebrated together. Students from fourteen African countries studied with us. As a symbol of Soviet Union-Mongolian friendship, we students from Mongolia were also invited to participate in May Day demonstrations.[2][3]

Handmaa (on the right) and her husband (third from right, front row) with other Mongolian “youth” whilst attending university in the City of Petigorsk. The placard, written in Russian (not Mongolian) Cyrillic, reads, “for friendship with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic (Rus. Soyuz Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respublik). Mongolia”. Photograph courtesy of J.Avrazed. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

It is through this small community of Mongolian students living away from home that Handmaa first met and starting dating her husband.[4] Both Handmaa and her husband (to be) were studying with a Mongolian stipend. At that time, it was sixty rubles per month. It was enough. Money brought a lot! We did not have to pay for our accommodation. It was free.

The rubles were spent on food and entertainment etcetera. The stipend for the students was on the basis of each individual nation’s contact with the Soviet Union. Students from (the African subcontinent) had a bigger monthly stipend than Mongolian students. Handmaa’s younger brother was also studying in Petigorsk at the Army College. Now he is also working in the South Gobi Aimag.

_________________________________

It is from these formative years of Soviet socialist enculturation that Handmaa’s adult life in Mongolia unfolded. it was from here that her ongoing involvement with the women’s movement and International Women’s Day [5] [6] was born. According to her husband, she has not only raised their children and worked as a pharmacist, but she has always been involved in public (read as, community) work. Such public work has continued to involve travel beyond the geo-political boundaries of the Mongolian People’s Republic.

After graduating in 1975 Handmaa worked until 1982 as Director and Specialist of the Pharmacy Administration Department of Dornod Aimag in Eastern Mongolia. When her husband graduated from the Institute of the Revolutionary Party in 1982, they relocated to the South Gobi Aimag where Handmaa worked for the next ten years as Director of the South Gobi Pharmacy Administration Department.

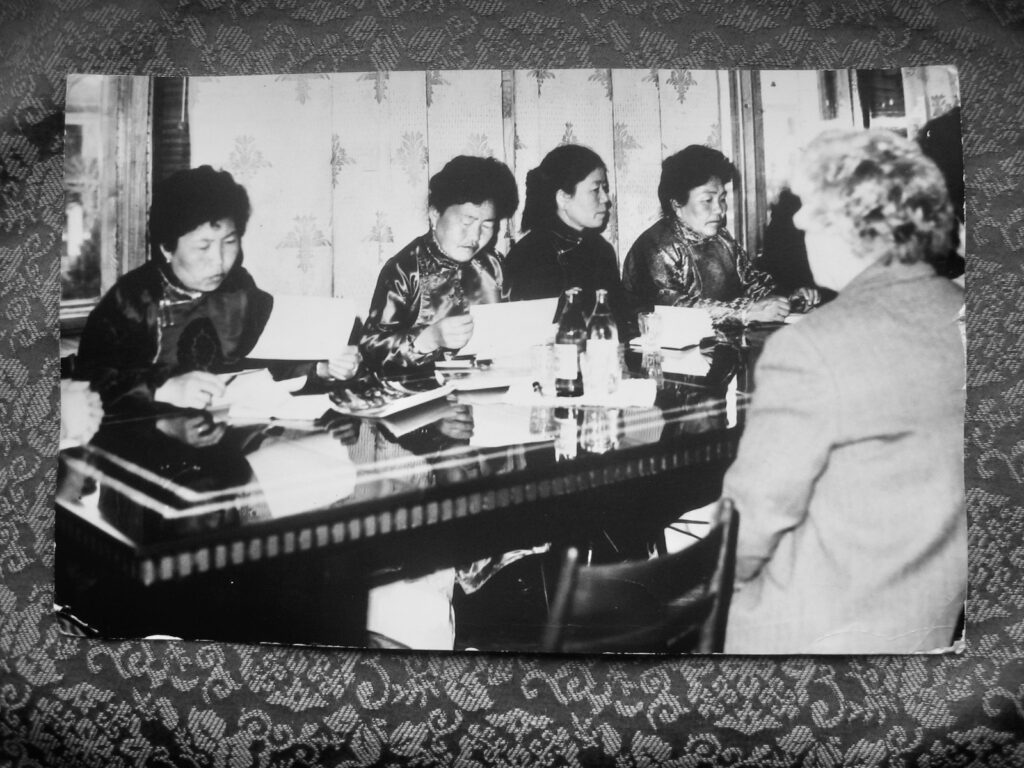

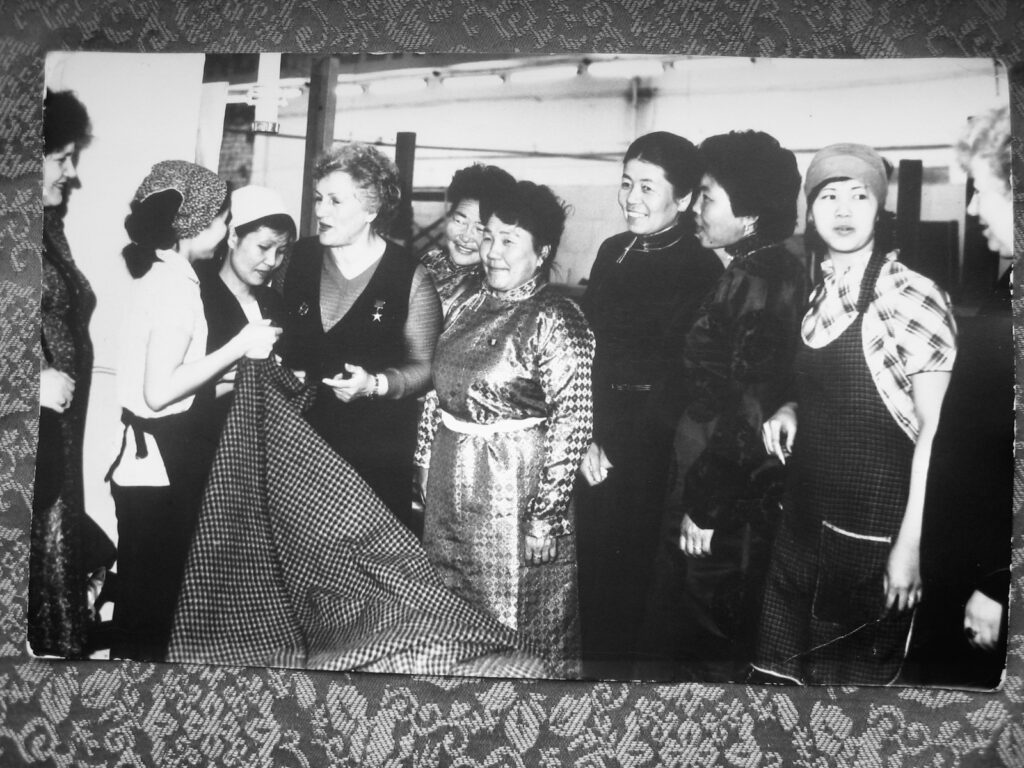

In 1985, delegates from Mongolia, of which Handmaa was one, were invited to visit a sewing factory in the now autonomous region of Khakhasiya in Krasnoyarsk. (see below). The population there are offspring of Mongols and have a friendship with us. One of the women who attended was Russian. She wore the medal for the Hero of Labour of the Soviet Union with the star on it. Another woman was from Tatar. The medal she wore has a different kind of star on it.

Visiting the sewing factory in Khakhasia in 1985. Photo 1 of 2. Handmaa (third from left). Photograph courtesy of J.Avrazed. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

Visiting the sewing factory in Khakhasia in 1985. Photo 2 of 2. Handmaa (centre right). Photograph courtesy of J.Avrazed. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

From 1992 until 2000 she was the State Inspector for Quality of Pharmaceutical Drug and Bio-Products for the South Gobi Aimag Governor’s Department of Professional Inspection. Not only is Handmaa a qualified pharmacist, but she also has an extensive knowledge of Mongolia’s indigenous plants and their therapeutic properties. In 2000, on top of her other duties, she established the Pharmacy Supply Company Limited in South Gobi Aimag and has been the Director of that company ever since.

In Mongolia, Handmaa has been presented with so many medals for her community work over the years. In addition, she was the Head of The Women’s Association of Mongolia for many years. Her medals include that of Best Worker for Health Security as well as Honored Worker for the Women’s Association.

Mongolian women of Handmaa’s generation can still be seen wearing their soviet-era medals, pinned to the front of their deels when attending important (to them) occasions and public events. However, this practice, along with the sign-posting and societal acknowledgement that would have accompanied such public displays of an accumulation of community-based merit, was disappearing (cf. 2008) and along with it, the social recognition and visibility of older women it once afforded. Where there is an intersection between other women of this generation and the Mongolian military, such medals continue to be worn. However, although she has many in her collection, Handmaa prefers not display any of these at public events.

______________________________

Handmaa and her husband receiving the Best Family-Household in the South Gobi Aimag award in 2008. Official photograph courtesy of J.Avrazed. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

In 2008 our family was chosen as ‘the best family-household in the South Gobi Aimag.’ We were awarded a cup as well as a certificate … for our caring for each other in the family, as well as helping others outside the family whilst at the same time working full-time.[7] My husband is Zavaa Damdin Rinpoche’s uncle. They are very close.

Both my parents were Buddhist people. My own father was not a lama, but there were lamas among the brothers of both my parents. They were all killed. They were shot dead in the religious purges of 1937. I now always carry with me a very precious to me small icon, a Protector talisman.

When my uncle-lama was being taken to his execution, he managed to leave his Protector talisman safely hidden under a bush. He was my father’s oldest brother and was forty years old at the time of his execution. Here in the South Gobi, there were many monasteries and many lams. Much later my parents found it.

They kept it safely hidden and only when I was considered old enough, they handed on this precious family object to me for safe keeping. It was now for my protection. My mother is still alive. She is eight-five years old (cf. 2008). My father who was twenty-two years older than her [in terms of age, a not infrequent asymmetry in Mongolia] passed in 1975.

Handmaa’s close involvement with her extended religious family stemmed from the time of her courtship whilst in her early twenties (cf. 1970s). We were living together with Narantsetseg’s parents. You know, Mongolians have a very tight relationship among their children and parents. Zava Rinpoche’s father was a very outgoing person. They were both working. They had eight children.

At that time, Narantsetseg (also a pseudonym) was also working as a cook in a local kindergarten. We sometimes helped them. But after graduating from the Institute of the Mongolian Revolutionary Party, we were both sent to South Gobi Aimag by the Mongolian Minister for Health. When we entered the Institute we both pledged that wherever the country needed us, then that is where we will go to work.

After only four years in the South Gobi, my husband was sent to Ulaanbaatar. They did not give me permission to go with him and so I stayed in the South Gobi with our two children. This was a difficult time for us at work because, prior to the move, we were both working for the same organization. He was working as the head and I was a specialist in the same organization.

According to the labour law at the time, a husband and wife were not allowed to work in leading positions at the one place. So my husband studied again and changed his work.[8] The need to adhere to this principle was very strong. We were both very highly educated and they did not give us any vacation from work because there was so much for us to do.

Whilst her husband was in Ulaanbaatar, Handmaa not only worked fulltime whilst raising two children who at the time were aged two and five, but she was also required to work as a translator for the Committee of the (Mongolian) Revolutionary Party and the Russian Army unit with which it was associated … Because of the close relationship with Russia at that time, there was always some event where Russians were present and where I had to therefore work.[9]

Handmaa in time became a Party member. The membership rules and all of its procedures were so tight. I became a Party facilitator, bringing people together and giving a speech about hygiene or introducing other important things related to Party policy. It was now the 1980s. By this time Handmaa, with her husband still required to live and work elsewhere, finally hired a young woman to help care for her two daughters whilst she continued to work.

Translating (from and into Russian) was kind of spontaneous work. I had to be a translator in many different situations. The Party meetings were particularly challenging, especially when Party leaders raised points that suddenly needed translating from Russian into Mongolian. At the same time my brother was personal interpreter to (Yumjaagiin) Tsedenbal (1958–1984), General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party.

People thought of me as an equally good interpreter as my brother. Indeed I was good in Russian because I always practiced [she smiles]. My brother did not like the idea of my getting involved in politics. My brother argued that for a woman, such work was too risky (read: dangerous for a person in a woman’s body, unstable and insecure in terms of ongoing employing.)

Eventually everything worked out. My husband graduated from his studies and returned to the South Gobi where we live together as a family along with my mother (cf. 2008), who although now in her 90s, she contributed to the sewing of the woollen covers for the twenty-panelled Mongolian Ger temple at Delgeruun Choira prior to its official opening in 2005.

Handmaa’s mother helping cut out and sew the felt panels for the new ger-temple at Delgeruun Choira/Soyombot Oron in Delgertsoght Sum in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. 22 August 2005. Photograph: C.Pleteshner.

___________________________________

Handmaa remembers clearly how she worked out that her new husband’s family with practicing Buddhists when she was first introduced to them in the early 1970s:

Oh, it was just visible! There was the ‘burkhan tahil’ (an altar) that caught my eye. They were such warm, kind people. I just felt something different in them. It was apparent to me that they had inherited religious things from their own parents. Just entering their home, its was visible… later, Zavaa Damdin’s father had friends who practiced Buddhism. They gathered one or two times each year … we all knew when, so we came to participate and to prepare things. My husband inherited religious things from his father. The whole family has been keeping and continuing practice without any interruption even during that time when it was very difficult and everything was prohibited.

In contemplating the meaning for her (of being a Buddhist family), Handmaa emphasizes:

… the need to support and help someone who is doing good deeds for others … If there is some event, I wish to be part of it, even though I have so much work to do back home. Either I come myself or I give some contribution. If my own deeds are good, it will influence my children and grandchildren. They will benefit from the fruit of my efforts. This is how I do things.

We Mongolians say practicing is better than just learning theory … many people come to Delgeruun Choira for the first time. They know nothing about the rituals, or where to put their Prosperity vases, or how things work, or what they should think and do. We should take the time to explain things to them properly. If we do that, then they will learn well. On the other hand, some lams from other places just turn up because they may have heard that there is a puja here (cf. Delgeruun Choira). They can earn some money. People are different. You know, in the long run, this would be bad for them.

Here, we are working together as a community, with one common wish. We have strength and so we have everything. For us, nothing has changed. We have been practicing Buddhism quietly, even though it was forbidden. Even though it was a hard time, we continued our practice. We lit a candle every evening.

We did it quietly. In the early days, Ganden Monastery was the only place for Mongolians to practice Buddhism in public and so we went there too; twice a year, every year, to pray. But in the early 1990s we had our first public Buddhist ceremony in the South Gobi. By then we had stopped going to Ganden. We only went there during the socialist times.

During those years, there were so many folk at Ganden in Ulaanbaatar, that no one ever recognised me. I was just a woman from the countryside, somewhere. My husband was a member of the Party, so he did not go, but I went there, and I would go there quite often. My thinking was that everyone should go to Ganden that is associated with the Government at least once a year; so as to get rid of all the potential obstacles for the coming year, as well as to pray for general and wide-reaching well being for everyone in the year ahead. Ganden was open to provide a public service to the nation. Now we have the freedom to do whatever we want, to go wherever we wish.

_____________________________________

Observations

Over the years, I have come to the conclusion that ‘Mongolia’ is made up of highly-contested and often congested and overlapping social spheres. From one perspective, buddhist revivalism is now just one ‘enterprise’ amid a plethora of competing others. So too are pharmaceuticals in this context, both their procurement as well as their dispensation. A market economy by design is a competitive place. It is in this post-socialist restructuring turbulence, that Handmaa still manages to continue to work and make her own way.

Moreover, she continues to be successful. She has negotiated (demonstrated leadership in) the difficult transition from socialist to post-socialist Mongolia. In this new ‘free market’ socio-economic sphere, she continues to be a credible, ethical and professional player. Here, as well as abroad, she moves deliberately, dipping into her extensive repertoire of performative (social) modalities to make things happen. In appearance, always healthy and friendly, she is neither drawn to particularly feminine nor masculine displays. Handmaa is always on the move, making the long journey from the Omnigovi (her home) to Ulaanbaatar, or to Delgeruun Choira, or to another country and back again.

I have personally observed over many years how Handmaa, consistently and effectively, deals with asymmetrical power relationships, be it with higher echelons of Mongolian socio-political and business strata, or in relation to interpersonal transactions with Mongolian people some would deem of another ilk. Doing any kind of business in contemporary Mongolia can be viewed from the perspective of a market economy. Handmaa reads and functions well in such settings dominated by embedded social hierarchies and their relative rankings. In terms of the Mongol-Tibetan interface of Buddhism in Mongolia? If control of the rules to be applied in such social settings, where an adherence to accepted protocols associated with religious hierarchies and social rank are a necessary prerequisite to maintain personal agency, then Handmaa knows and embodies them more than well.

Her people networks, going back generations in Mongolia and global in other spheres, are well-established. Robust and at this stage of her life, they are now extensive. She teaches. She studies. She practices. She attends international conferences. She “does” pharmacy. She does business. She travels to cities in the Russian Federation (cf. 2008) as well as to Beijing and elsewhere around the world on her particular business. With her sisters, she convenes local ‘development’ workshops. She takes both professional and organizational collaboration and development very seriously. This is what she does. She has not, and does not waste her time. And like others in her professional clique, she considers making a contribution, vocational and volunteer, to my Mongolian society important.[10]

I’m not one to regularly sing such high praises, especially when I’m supposed to be doing ‘ethnographic and qualitative research’. But some people are special, aren’t they?

_________________________________

Now let’s fast forward 15 years from 2008 to 2023

Celebrating “World Doctors Day” in the main Ger-Temple, Soyombot Oron (Mong. Соёмбот Орон) in Delgertsoght Sum in the Gobi Desert. Mongolia’s Honoured Doctor J. Tseveenjav (on left), Zava Damdin (centre) and Mongolia’s Honoured Pharmacist N. Myadagmaa, our “Handmaa” (on the right). 30 March 2023. Reprinted on CPinMongolia.com with permission.

As Zava Damdin Rinpoche summarised (FB 30 March 2023), sister Tseveenjav has performed ear, nose and throat surgery on more than forty thousand people without an accident. I think she’s a living legend! And my sister Myadagmaa? She has such a very kind heart. No one has ever seen her angry, even at this age. She is still dispensing medicine to so many people. She too is considered a living legend!

_________________________________

An embodiment of contemporary Mongolian womanhood

Is N.Mayadagmaa’s now life-long engagement with, and concern for others, the “doing something”, traditionally Mongolian? Or is it something Buddhist? Or could it be an embodied reflection of a productive and personally-fulfilling socialist past?

I suggest, that these perspectives are not in contradiction. Whichever schema one chooses to frame the consideration of Myadagmaa’s activities in the public domain, she not only embodies a highly-refined socialist ideal of community service, but for me she also embodies the Buddhist ideal of joyous effort and perseverance [read as, consistent and persistent hard work] for the benefit of others. In the words of her own Mongolian women friends, she is a determined and formidable person! Is this traditionally Mongolian? I’ll leave that for you to decide.

_________________________________

Footnotes

[1] For study interviewees, ‘place of birth in Mongolia’ appears synonymous with cultural ‘background’. This conflation requires further research.

[2] Although the term ‘demonstration’ has come to be more closely associated with notions of protestation, a number of interviewees used ‘demonstration’ and ‘celebration’ interchangeably in their conversations with me. I understood their intended meaning as being that of an outward display of harmonious (international) relations performed by, and for, the soviet press at the time.

[3] Specific reference was made to the May Day celebration held in the city of Krawsnodar in Kuban on 1st May 1973.

[4] They had first met in the Irkutsk Oblast (Russian: Ирку́тская о́бласть, Irkutskaya oblast) of what is now the Russian Federation. Irkutsk is both a city and a region in South-Eastern Siberia.

[5] Originally named International Working Women’s Day, International Women’s Day (IWD) is celebrated on the 8th of March every year, observed firstly in economically expanding and industrializing Germany in 1911. See: T. Kaplan, On the socialist origins of International Women’s Day. Feminist Studies 11, No. 1 (1985), pp. 163-171.

In 2008, when this key informant interview was conducted, a range of region-focused aspects of womanhood were celebrated along with social, political and economic achievements of certain women in particular regions, as well as women (as a category of person) in general. 2011 marked the Centenary of IWD.

However IWD came to prominence as a political event where, along with it already being officially promoted in the former Soviet bloc countries as an event where different cultures could be conflated, as reflected here in Handmaa’s narrative, IWD was decreed on 8 May 1965 by the USSR Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (Russian: Президиум Верховного Совета or Prezidium Verkhovnogo Soveta) as (also) being,“in commemoration of the outstanding merits of Soviet women in communistic construction, in the defence of their Fatherland during the Great Patriotic War, in their heroism and selflessness at the front and in the rear, and also marking the great contribution of women to strengthening friendship between peoples, and the struggle for peace.”

[6] On the topic of International Women’s Day: We name the holiday Олон Улсын Эмэгтэйчүүдийн Баяр. It is one of Mongolia’s six official non-working public holidays (cf.2008) … I know for sure that the Mongolian celebration of Women’s Day has a connection with the celebrating of International Women’s Day in the West. We call this holiday an “International Women’s Day” and celebrate every year on March 8. It is still celebrated as a (Mongolian) State holiday which is a non-working day.

During the socialist period it was a day to mark outstanding achievements and contributions of women in initial socialist construction. But nowdays this holiday has lost its political flavor, and has become mostly an occasion for men to express respect, appreciation and love towards women in their own family’s circle. But in the ‘most wide range’ [read as: in broadest terms] it is a day to celebrate women’s achievements in all social and cultural areas of life. So women get awards on this special day from the government, and from businesses where they work.

[7] Handmaa’s husband also has earned many medals acknowledging his contribution to his community. These include, The Altan Gadas and The Northern Star. These medals were awarded on the 70th and 80th anniversaries of the People’s Revolution in 1921. Then there is the Order of Hero of Mongolia, the Order of Sukhbaatar and the Order of the Red Banner which is the third highest award and that was presented in 2003 by the Mongolian President Bagabandi himself. Handmaa’s husband has also has been presented with awards such as The Gold Star from the Association of Mongol-Russian Friendship from Russia.

[8] It is interesting to note here that it was not the other way round.

[9] Handmaa held down a high position with its many responsibilities. Yet there seems to have been little support available to her in the way of child care, although in emergencies (she) would occasionally ask neighbors or friends.

[10] In 2008 my interview with Handmaa at Delgeruun Choira was cut short to enable her to drive to Ulaanbaatar in time to catch her flight to Beijing where she was attending another International Women’s Forum.

_________________________________

Attribution

This vignette, like others in this series, is grounded in my ethnographic fieldwork (2004- ) and interviews with the person about whom I write. All of the people in this assemblage are Khalkha Mongol, the largest group of ethnic Mongol peoples living in Mongolia today. See: Pleteshner, C. (2011). Nomadic Temple: Daughters of Tsongkhapa in Mongolia (Unpublished manuscript). The Zava Damdin Sutra and Scripture Institute Library Archive in the Manjushri Temple, Soyombot Oron).

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating the photographs, using or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article, then you may also enjoy:

Please refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2025. CP in Mongolia. This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 10 March 2024. Last updated: 11 March 2024.