Jantsan Gundegmaa attending a luncheon to break the long drive back to UB from Delgeruun Choira in the Gobi Desert. In 2005 before the north-south (Russia to China) road was constructed, this journey took between 7 and 10 hours each way, depending on the weather, the condition of the Gobi desert tracks and how many cars (old and new) and passengers were in the convoy. 25 September 2005. Photograph C Pleteshner.

Since 2004 I have observed and participated in how Mongol-centric cultural, political and social approaches have (re)emerged or adapted to revitalise local traditions and practices after Soviet socialism (1921-1990) in Mongolia. This post links my previous articles about contemporary Mongol women, culture and society, to other analyses and vignettes to be published here in the weeks and months ahead. In particular, this post brings forward into a post-socialist present, aspects of Mongol women’s enculturation and embodiment discussed in Artscape 07.

During my initial years of fieldwork in Mongolia my focus was on researching the cultural and religious practices of contemporary (living) Khalkha Mongol women in the reconstruction and revitalisation of Mongolian Gelugpa Buddhism in Mongolia. However there is no moving forward without understanding at least something about the past.

In response to requests from friends and colleagues I have begun publishing more of the articles I have already researched and written on this topic. Some short, some long, they will be posted to one or other of the e-site branching categories of my dual platform (website and You Tube) blog. (I am pleased and relieved to say this initial information design as implemented when I first started blogging back in 2014 continues to work well for my narrative styles and interests).

With my next series of posts, the educational objective is to give interested readers greater ethnographic traction with this aspect of Mongol women’s lives. In so doing, to cultivate a more nuanced understanding of how embedded (and important) their personal accounts of events and experiences (i.e. memories) are in the situated-ness from whence they arose. In Mongolia, such detailed information lives on in kinship network settings. As outsiders, we can get a glimpse of it here, even though most (but not all) accounts will be de-identified for reasons I have elaborated in a previous post.

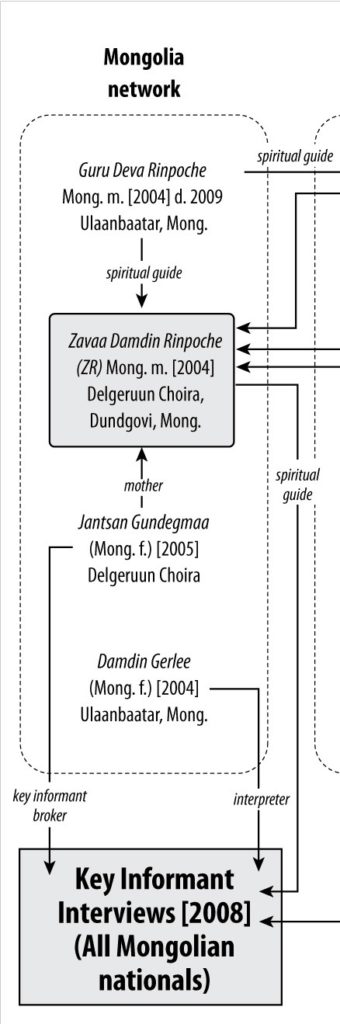

Diagrammatic representation of the Mongolian women’s study 2004-2011 participant recruitment frame (In Mongolia Section). 19 July 2011. C. Pleteshner

Indigenous Khalkha Mongol women’s voices drawn from the one community of practice, that associated with Dugarjav Osgonbayar (Luvsandarjaa) Zava Damdin Rinbu̇ u̇ chi (1976- )[i] in the lineage of the ethnic Mongol Lobsang Tenzin Gyatso Pal Sangpo Guru Deva Rinbu̇ u̇ chi (1910-2009)[ii] are the primary source of this particular enterprise. As a collection, the personal narratives and specificities found in these Mongol women’s voices differ from those grounded in similarly designed qualitative anthropological studies about women elsewhere. Together with my interpreter Damdin Gerelbayasgalan (Gerlee, no relation), Jantsan Gundegmaa, Zava Damdin Bagsh’s own ‘blood lineage’ mother, were essential to the success of this otherwise onerous cross-cultural study participant recruitment task.

Jantsan Gundegmaa at home in Ulaanbaator sewing another silk brocade cover for an old sutra discovered in a Mongol family’s commode. People come from all over Mongolia to Zava Damdin with their precious letters and old now crumbling pecha-texts for insight into their meaning, purpose and content. Using her sewing machine and skilled handiwork, J.Gundegmaa ensures they leave with their precious artefacts wrapped in carefully sewn silk. 7 October 2014. Photograph C.Pleteshner

One important point of clarification. The current post-soviet socialist period of rapid and chaotic social change in Mongolia (driven by local, regional, globalising forces and the extreme weather) continues unabated. To put at least some parameters around such confluence and fluidity for readers, in the forthcoming series of articles we are concerned with Mongol cultural life specifically through the lens of Mongol women’s voices and other data I collected in-the-field in Mongolia between 2004 and 2011 concerning them.

These Khalkha Mongol women’s perspectives (along with my own) that were recorded and coalesced around this specific lineage of Buddhist practice in Mongolia during this time and place (an abundance of specific time-place situated-ness), have of course since shifted; not necessarily moving away, but nonetheless transforming into individual and Mongolian kinship-centric arrays of unfolding contemporary continuity and other-ness. Like bubbles on a fast moving stream, the events, perspectives and accounts that were recorded are now history, artifacts and snapshots in ethnographic research time. Herein lies their value!

Now, for the sake of ongoing continuity let’s fast-forward for a moment to February 2018! As you can see from the photograph below, whilst I continue to publish stories about what has already happened, these diligent and very focussed Mongolian people continue to lead their own way!

Jantsan Gundegmaa (seated on the right) with her (now) 3 generations of post-soviet socialist Khalkha Mongol lamas. This photograph was taken in the Teacher’s ger at Delgeruun Choira in Delgertsogt Sum, Dundgovi Aimag. 26 February 2018. Photograph courtesy of The Zava Damdin Scripture and Sutra Institute of Mongolia.

Having rebuilt Delgeruun Choira in the Gobi Desert (2004- present) a new school for young lams in Ulaanbaator is now under way. Of course, as is the way with all modern day ‘developments’ in Mongolian society, there are complicating backstories, setbacks, ‘gossips’ and other intrigues associated with this otherwise apparently linear process. I’m sorry to disappoint, but these are of relatively lesser importance here. For now I am primarily concerned with bringing more individual Khalkha Mongol women’s voices to our cross-cultural discourse table. Hopefully you’ll find something of interest there.

Footnotes and Supplementary Explanations

[i] To facilitate a greater appreciation by readers less familiar with contemporary Mongolian society (i.e. non-nativist scholars) of some of the nuances associated with people’s names and their appropriate uses, I would like to offer the following illustrative summary of what is otherwise a complex inter-cultural linguistic topic:

In Mongolia, the person we know as ‘Zava Damdin Lama’ (generalist and accessible Anglicised version, for example) is referred to by other names that are context dependent. These include: (i) Zava Damdin bLo bzang rta dbyangs (1867–1937): the name ‘Zava’ was offered by scholars and other wise people at the time. ‘Damdin’ is his given name from his father and mother.’ bLo bzang rta dbyangs’ is his fully ordained monk’s name. This is one example. There are other names; (ii) Zava Damdin Lama (1976– ): this name was used after formal recognition in Mongolia as a reincarnation of the previous Mongol Zava Damdin (see above); (iii) Luvsan Darjaa Perenlei Namjal (1976– ): this name was bestowed at enthronement; an official reincarnation name; (iv) Zava Damdin Rinbu̇ u̇ chi (or Rinpoche) (1976– ): this is a shortened name given at enthronement; (v) Zava Damdinii Huvilgaan (or Tulku) (1976– ): another name sometimes used by people in Mongolia; (vi) Zava Damdin Luvsandarjaa (1976– ): this name is used in academic, research and other official documentation; (vii) Lobsang Dargey Zava Damdin Lama (1976– ): a variation on the above; (viii) Luvsandarjaa (1976– ): this is the fully ordained monk’s name. ’Lobsangdargey’ is a Romanised Tibetan rendering of the Mongolian ‘Luvsandarjaa.’ (ix) Dugarjav Osgonbayar (Luvsandarjaa) (1976– ): ‘Dugarjav’ is Zava Damdin Lama’s Father’s name. ‘Osgonbayar’ was the name given to Zava Damdin by his grandfather Buyan Sharav; (x) Zava Bagsh (1976– ): people in Mongolia, and people who have a Mongol cultural background sometimes use this less formal abbreviated form; (xi) Bagsh (or ‘Teacher’) (1976– ): whilst still respectful in tone, this is a very abbreviated form often used in Mongolia; (xii) Zava Lama (1976– ): people in Mongolia and in the West with an interest in Tibetan Buddhism sometimes use this less formal abbreviated form to refer to the Mongol Gelugpa Lama, Zava Damdin Rinpoche.

Whilst the actual use of a particular name is dependent on the nuances of social, cultural, performative and literary contexts, the various names and honorific titles for the Mongol person known as ‘Zava Damdin’ can be seen to fall into one or more of the following applicable onomastic categories: (a) historical names; (b) a given name; (c) a family name; (d) a monk’s ordination name; (e) a reincarnation’s name; and (f) a respectful name, formal and less formal.

This list of names is by no means complete. In addition to Romanised English, there are other scripts and languages: Mongol Bichig, Russian Cyrillic, spoken Mandarin and written Chinese Cangjie ideographic script, written Japanese (a combination of logographic kanji and syllabic kana). University-trained scholars in the West with a background in Tibetan (rather than Mongolian) Buddhist Studies and other observer-commentators may use other permutations that are more aligned with the standardising conventions of their own literary output, university departments and publishing establishments.

Returning to how different names for the same person are used in Mongolia, in The Great Nenchen (pp113-116) Zava Damdin Lama has assigned a particular personal ‘signature’ (cf. name) to each of his beautiful songs. This can be interpreted as not only an explicit reflection of the aspect of socio-cultural relationship-life he has chosen to foreground, but at closer examination, it also reveals the deeply inter-personal and hence spiritual-performative location from which the song was born.

[ii] When I last discussed this topic with Zava Damdin Rinpoche, just after he completed his four year solitary retreat in 2012, in addition to Guru Deva Rinpoche, he then also noted seventeen other specific ethnic Mongol and Tibetan individuals as his lineage Teacher-tutor elders.

Rinpoche’s own ‘born of bone’ father Dugarjav (born from his grandfather Buyan Sharav, a devout Buddhist whose own three lama brothers was executed during the widespread religious purges in Mongolia in 1937), Tibetan Lharampa Geshe Dayang Thubten Trinley (1933- ) and His Eminence Jetsun Tendzin Kaedrup Jigme Namgyael Gonsar Tulku Rinpoche(1949- ) Director of The Centre des Hautes Etudes Tibétaines (Centre for Higher Tibetan Studies, originally named Tharpa Choeling) and founded by Geshe Thubten Rabten Rinpoche (1921-1986) in Switzerland in 1977, were never far from his mind’s eye as he spoke of them with gratitude and deep respect. Here, in Europe, commentaries and discourses given by in-residence qualified and learned Masters are conveyed simultaneously in four languages: English, Tibetan, French and German. This is achieved through a combination of wonderful translators (Marie-Therese Guettab, French; Helmut Gassner, German) and state-of-the-art digital platforms and communication technologies. Significant ground has also been broken in terms of translating texts into both Russian (Cyrillic) and Czech by others in residence. Teaching and learning in this network of centres is like having a front row seat at the united nations. Its a collaborative, grounded in both place and practice, embodied and multicultural affair. The extent and quality of the translation, app, e-book and hardcopy publishing output is considerable.

Landscape 05: Living Voices was researched and written by Catherine Pleteshner.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating or translating into another language all or part of this article or the photographs, and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2024. CP in Mongolia. This post Landscape 05: Living Voices is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 7 August 2018. Last updated: 20 June 2022.