As I continue to travel back and forth from Mongolia, friends in Australia and other parts of the world have asked the same question: ‘What is it like in the Gobi? What is it that you do there again?’ In this post I take you back to 2005 to what turned out to be a watershed experience, an important turning point in my own small life.

Background for Departure (past tense)

Two thousand and five (The Year of the Rooster) was the first year I travelled to Mongolia on my own after being invited by Zava Damdin Rinpoche (1976- ) to return, stay and study with him at Delgeruun Choira in the Dundgovi for 3 months at the conclusion of my first 3 week visit to Mongolia the previous year (2004). Back in Australia, at the peak of my career I was still working full-time in health informatics, but had accrued enough annual leave and good will with my wonderful boss and long-time family-physician colleague and friend Pof. Peter Schattner. It was he who enabled and supported my retreat from our otherwise high pressure routine informatics research life possible. It was he who kept my position open for my return. For this kindness, I will forever be grateful …

Mongolian Nadam (here and now)

This weekend (11-15 July 2019) here in the Dundgovi (abbrev. Gobi) it is ‘Nadam’ or ‘the Games’, the modern Mongolian and Inner Mongolian form of an ancient Kalkha Mongol summer festival (see Christopher Atwood 2004, pp396-397). Whilst current pan-global stereotypes (especially for international tourists) may impute horse racing, lots of dust and the excesses of celebratory food and alcohol consumption, ‘locally’ there is much more to this established cyclical annual celebration than at first meets the eye.

During their extended Summer vacation (July-August) Kalkha Mongol people in a position to do so abandon their UB-town (as the international tourists flock in) and instead head out and away into to steppe, their countryside, to their dachas or other ‘sum’ venues to celebrate Nadam with their family and friends. I have observed this cyclical annual practice as one year has flowed into the next.

It is during these animated social situs that kinship-based social networks are consolidated and reformed. It is at these gatherings that ‘local’ stories are told and retold (with and without embellishment) as transmissions of cultural and other familial knowledge for present and future generations. This short post to my blog is an echo of this social practice.

Mongolian Nadam (an historical overview)

Be it in large or small groups, since the 17thCentury, the ‘three manly games’ (Mong. eriin gurwan naadam) of the Mongolian Koumiss summer celebrations (with wrestling, horse racing and archery competitions) have taken place.

In 1912, these ‘danshug’ games were officially rescheduled to the last lunar month of Summer (July-August) and included everyone not just Khalkha Mongols. In 1922 the new government limited, and then in 1923 eliminated, this public celebratory gathering altogether. In 1924 Nadam became the National Holiday Naadam (Mong. ulsn ikh bahar naadam) now a secular national holiday celebrating the achievements of the new post-revolutionary nominally secular state.

From the late 1930s, during the Soviet socialist era, wrestling and archery events were relocated from open fields to stadiums and more resembled Soviet-style political celebrations. Since 1990, now that attendance at ‘Nadam’ is no longer compulsory, Mongolian people in the nation’s capital either watch ‘the performance’ on television and/or leave the metropolis to celebrate Nadam with family and friends in provincial and sum (district) centres out on the steppe away from UB-town. Mongolian people I know just love a good picnic! In the weeks before this long weekend, Mongolian women in my circle spend considerable time ‘preparing sheep’ and other home-made foods and delicacies as offerings of good will etc to other family members and friends during Nadam gatherings.

English Lessons, Khavsai and Youthful Masculinity

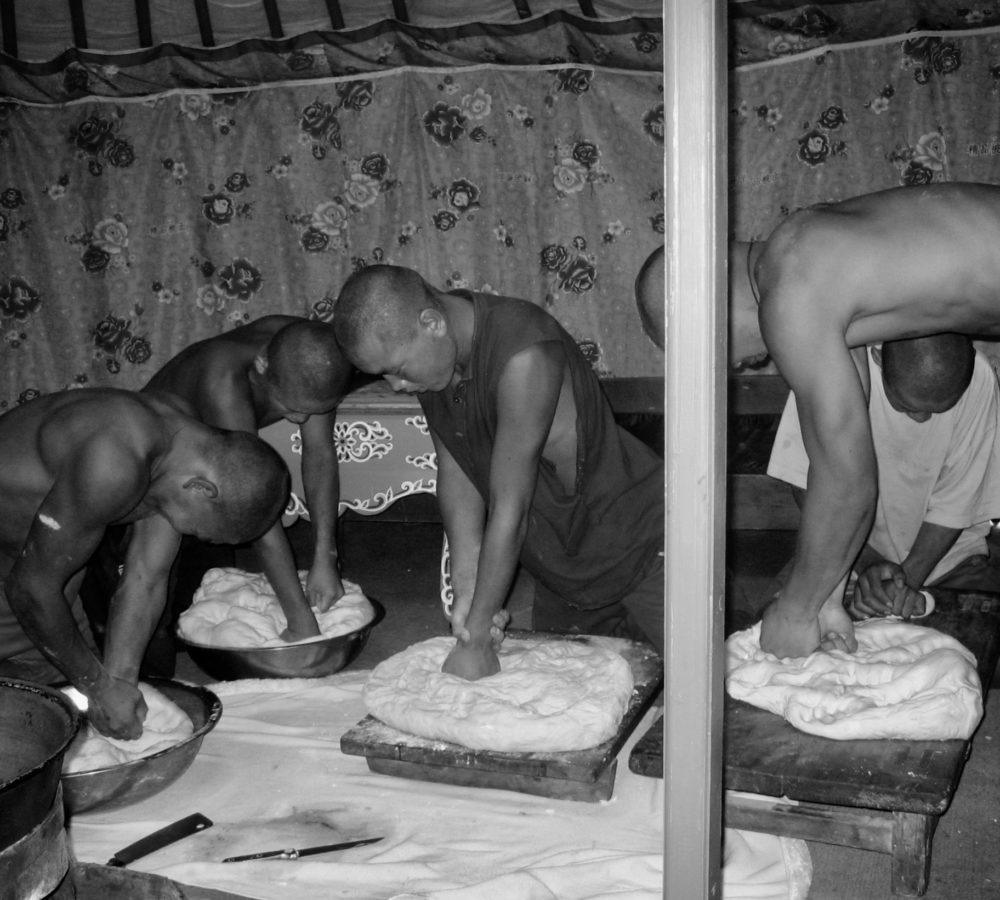

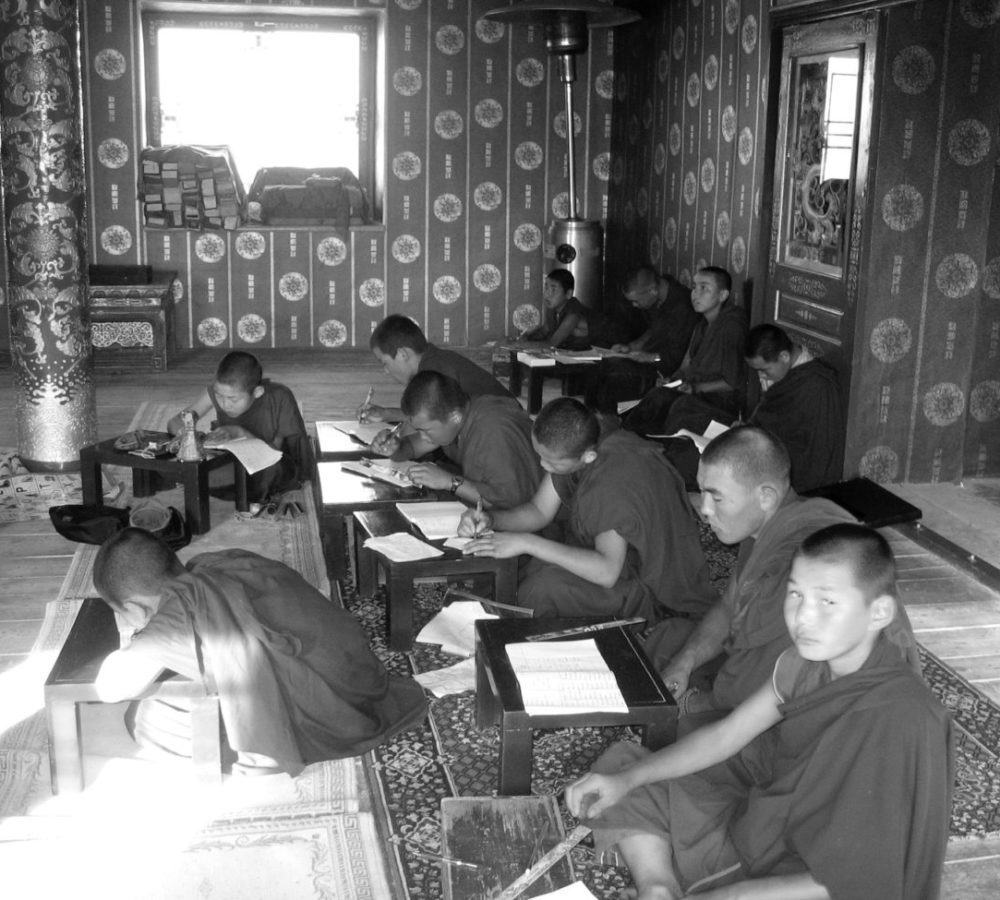

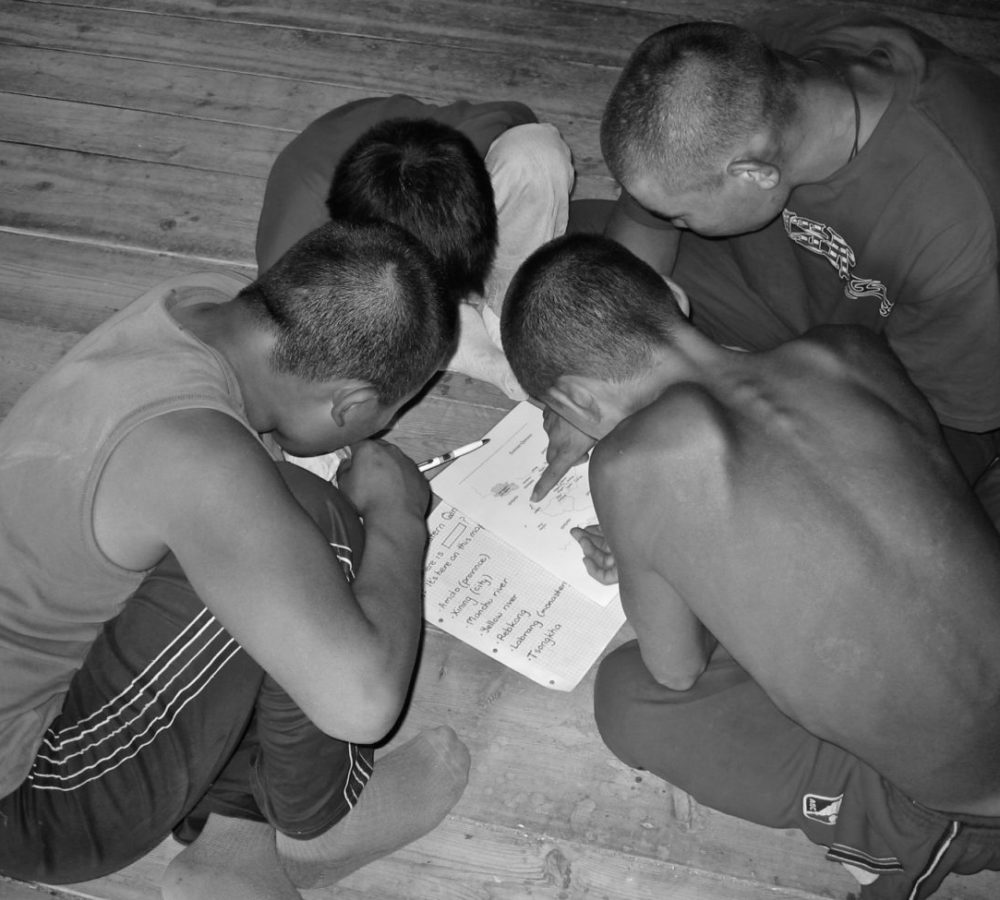

So why the introduction to Nadam as the preface to this post? Because I wanted to contextualise and then highlight for you the sheer physicality of what may now be a Mongolian-in-Mongolia recent socio-religious past. With no electricity, these Khalkha Mongol Delgeruun Choira boy-lams, not only attended my daily english language classes at the end of their long hardworking days, a couple of extra hours on top of an already busy day, every day for 3 months, they also kneaded dough by hand (for many hours over a couple of days) for khavsai, a leavened bread made from wheat flour especially for Mongol Buddhist religious ceremonies and special events.

Whereas in a more formulaic showcasing of UB-Nadam ‘sport’ where embodiments and expressions of masculinity (in particular wrestling) are foregrounded and isolated away from daily life, the above image of a contemporary Mongol youthful masculinity integrates not only a local expression of their physical strength and determination, but also the sense of teamwork and friendly competitiveness displayed and palpable at the time. Surely, this is in keeping with what the (traditional) spirit of Nadam is all about?

Notes about the photographs

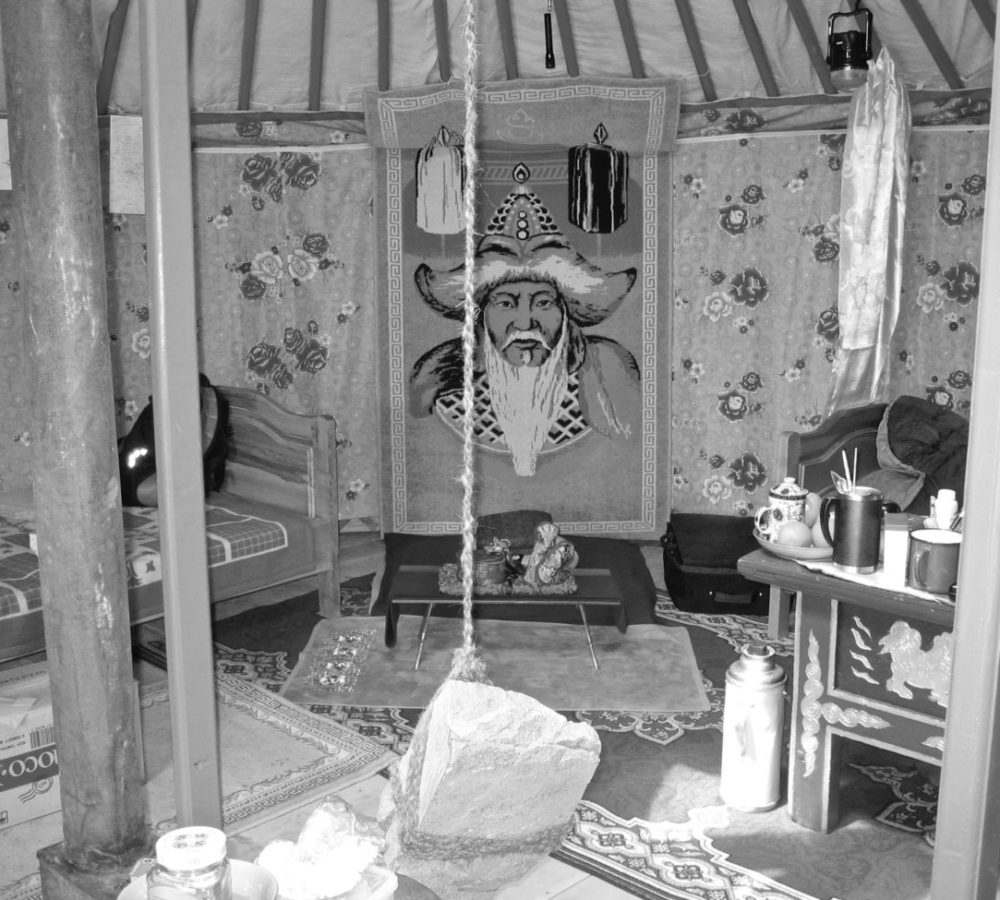

This was the Summer of 2005, the year that the reconstruction of Delgeruun Choira infrastructure in Delgertsogt Sum in the Dundgovi started gaining momentum. The need for sustained physicality (lifting, moving, digging, rolling, painting etc) was at the fore – for everyone. So what did I do? Well, mostly I swept, took photographs, became a tour guide when necessary, engaged with local people and a seemingly never-ending stream of interested visitors, attended daily Lam Rim classes and evening pujas, and taught English.

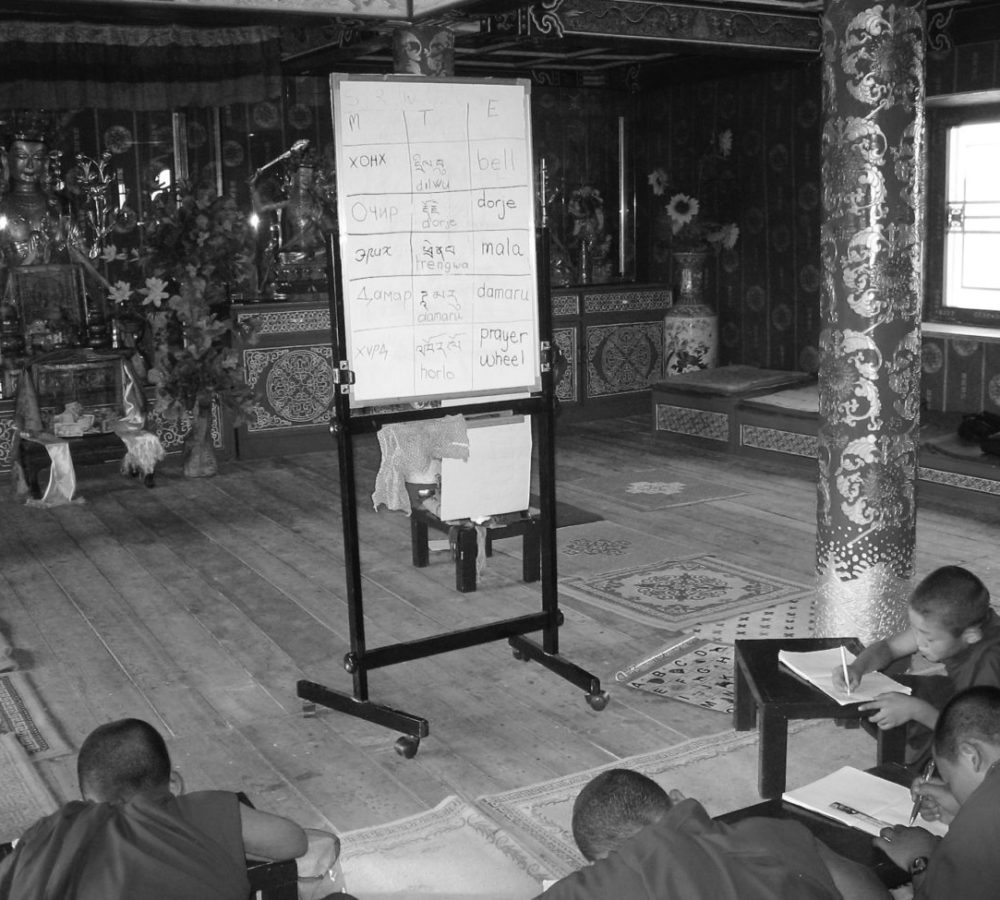

Sand out here in the Gobi never stops moving. It finds its way into everything! A momentary gust of wind can annihilate 3 hours of sweeping sand out of the ger-gompa! I taught English to DC lams together with other local (Delgertsogt Sum) children, girls and boys, (in the above photo, the one with longer hair). Tuition started in the ger-classroom (our first classroom!) and then moved to The Temple of the Five Manjushris once the timber floor had been laid down.

The whiteboard had been donated by B.Surnaa. With no electricity except for one petrol-driven generator for power tools, nor phone, nor internet, this whiteboard was considered pretty high-tec at the time! I also gave English lessons in my own ger once it had been rebuilt by our local Mongolian friends after being nearly blow away during one of the Gobi’s famous albeit now less frequent torrential rain-strong wind storms. You know the ones: those that blow down from Siberia and the north-east and that leave a trail of broken or torn everything that happens to be untethered in its way. During that same wind-driven deluge we also nearly lost the newly-erected and huge Shining White Palace Gompa-Ger but that is another story for another time.

CP preparing English lessons whilst waiting for a ride in the reception area of Guru Deva Rinpoche’s House in Ulaanbator. 8 October 2005. Photograph courtesy of Lobsang Pagchuk

References

Atwood, Christopher Pratt. 2004. Encyclopedia of Mongolia and The Mongol Empire. In Facts on File Library of World History. New York: Facts on File Inc.

This article Landscape 10: Teaching and Learning in situ circa 2005 was researched and written by Catherine Pleteshner.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating the images or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2024. CP in Mongolia. This post Landscape 10: teaching and learning in situ circa 2005 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents embedded or linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 15 July 2019. Last updated: 20 June 2022.