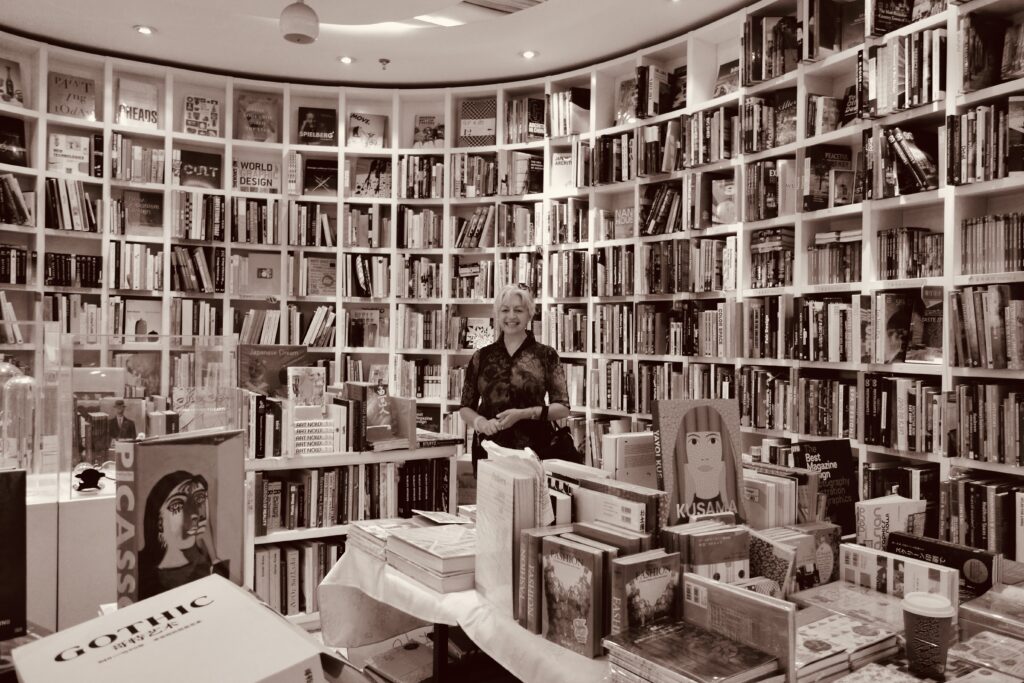

CP ‘at work’ in the fine arts and design section of a favourite bookshop in Beijing. There’s no substitute for browsing through interesting yet unfamiliar books to enliven the heart and broaden the mind. 12 May 2013. Photograph courtesy of L.Sampel

1. Roadmap

As an excursion from studying the art of translating Zava Damdin’s (1976- ) insightful poetry from the Mongolian language (see INDEX), I felt the need to now gain at least some appreciation of the underlying fundamentals of Chinese poetics as well. They are neighbouring cultures after all, and so …

The word poetics has two meanings: the art of writing poetry and the study of linguistic techniques in poetry and literature. Here, we are mainly concerned with the first of these. We begin this exploration by venturing into some of the social and aesthetic functions of the Confucian-inspired genre of poetry.

K. Wang’s Spirit of Chinese Poetics is the primary reference text from which I draw heavily, along with a few supplementary others (see below). There are many genres of Chinese poetry. This is an introduction to just one of these.

2. Poetry as Social Discourse

Poetry has long played an important role in the philosophical and cultural dimensions of Chinese society, with Confucius (551-479 BC) placing equal emphasis on poetry, music and ceremonial rituals in terms of one’s personal cultivation (xiu shen). Confucian logic emphasises the importance of developing one’s wholesome character, which can then affect the world around that person through the principles of cosmic and social harmony.

The term shi, in its centrality to this traditional Chinese poetic discourse, offers the nearest functional analogue to our western category of poetry. Shi can simply be translated as lyrics that express certain aims. Shi was also the name of the musical repertoire overseen by musicians of the Zhou court (1046-256) that was central to their curriculum of ritual and musical education.

Often sung to a musical accompaniment, songs, odes, lyrics, hymns and epics were part of important occasions and other social situations. In ancient China, poetry was also widely used by scholars as the primary modality for exchanging opinion and expressing values, in daily conversations as well as in diplomatic relationships. Poetry was also included in written essays and other forms of cultural entertainment.

In terms of the historical use of poetry in diplomatic settings, songs deemed suitable for such occasions were requested and sung by both hosts and their guests to progressively build a suitable ambiance of mutual appreciation.

In more contemporary terms, diplomatic or conversational, written or sung, public or private, formal or friendly, songs were used as ice-breakers to build understanding and/or rapport. Poetry as a social discourse was encouraged as a way of inferring (similar or differing) ideas or principles by those at the table.

In such settings, if you are someone who recognises the value of poetry as a modality of social discourse, especially in relation to cultivating the art of speech through ongoing study, then the art of the doing now pirouettes around selecting or composing the appropriate song for the social situation.

Accordingly, if it is to be consistent with Confucian thinking, such investment in individual development and its demonstrated refinement of taste (a nod to Bourdieu), should also be in the interests of community. Here, it is important to remember that in the Confucius’ era, poetry straddled both intellectual learning and aesthetic education, with music also not too far from the mix.

3. Poetry as Aesthetic Discourse

From this perspective because of its aesthetic values, poetry played a pivotal role in terms of personal cultivation. Why so? [Because] poetry is generally believed to be expressive of feelings and affections through its descriptions of both inner and outer experiences. It can be read, recited and appreciated so that one may get to the bottom of the message implied in the composition.

In terms of the aesthetic and artistic functions of poetry, Confucian logic foregrounds the idea that poetry can serve to inspire (xing), to reflect (guan), to communicate (qun) and to advise/remind (yuan) from the Latin admonere, for the benefit of not only oneself but for the benefit of others as well. Hence, these are the four main guiding principles that form the aesthetic discourse in Confucius’ poetics.

3.1 Poetic Xing (to inspire)

The main idea behind the Chinese notion of xing, is for the performance of poetry to move and uplift the mind towards virtue through aesthetic experience. During this process, the facets of understanding, imagination and contemplation combine and come into play, hence there is both an aspirational and inspirational dimension to xing.

As a poetic device, xing involves depicting a particular image or a particle object in a poetic style. When such poetry is contemplated, the imagination is stirred, and so too is the understanding of its contextual suggestiveness. A well known example in Chinese culture “peach trees”, invokes a (previous) culturally-specific ideal: for young people to marry in the spring when peach trees are in full bloom.

As an aside, in terms of cultural visual narratives and their associations, next time you watch a well-made Chinese historical TV drama on Netflix or other streaming service, keep an eye out for the purposeful use of iconographic representations of peach trees, their location, their blossoms and fruit. Look for the continuity between these.

After another cold winter, an ornamental cherry tree coming into full bloom in the extensive 190K sqm Boda Park with its integrated cultural and leisure functions in the B&TD district of Beijing. The park and its lake have been designed with innovative rainwater utilisation and energy-saving systems. 28 April 2013. Photograph: C.Pleteshner

3.2 Poetic Guan (to reflect)

There are layers of meaning and usage for the Chinese concept word guan. In general terms, guan is used to evaluate and appreciate poetry and other forms of art from an aesthetic as well as moral perspective. A taste judgement is always involved. In this context, guan’s function is intimately aligned with culturally-specific arts education and its values.

Guan also means to contemplate and to reflect shifts in social customs and mores over time. From this perspective, Confucian poetic creation arises from exploring and observing social environments and the human condition in relation to social mores.

Yet another idea, that of how “poetry can serve to reflect” (guan) suggests, if not assumes, that the poet has contemplated and judged their subject matter, both aesthetically and critically, as part of their own process of poetic reflection. This is also true for the reader as s/he examines the experience or event presented in the poetry, with or without the aspired to culturally-attuned awareness and sensibility.

“Poetry” as a form of arts education, implies that not only have the reader’s aesthetic needs and expectations been met, but that the reader or listener’s temperament is also in some way being honed through reflection. These reflective processes coalesce to facilitate a kind of nuanced sensibility with particular regard for the Confucian principle of “gentle and kind” character training, the Chinese, “wen rou dun hou”.

3.3 Poetic Qun (to communicate)

Qun is the Chinese word for social grouping or gathering. However, poetic qun has a broader meaning. The purpose of the qun aspect of Chinese poetry is to facilitate a two-way communication process for a range of social occasions (eg. feasts and diplomatic gatherings) in order to promote a friendly atmosphere.

From this perspective, poetic communication (qun) performs a similar role to music in the Confucian mind. It can create an engagingly harmonious climate, arousing human emotions in an attempt to awaken mutual understanding in order for concordance to arise.

Like music, this kind of poetic qun is inseparably linked to the concept of humanity (ren), since it runs counter to the tendency for people to form cliques to suppress or win the upper hand over others. The Confucian notion of poetic qun also indicates a sense of responsibility and commitment to drawing on poetry and its poetic experience to influence people’s thinking and character development towards harmonious relationships with others.

3.4 Poetic Yuan (to advise/remind)

Through reference to social problems, Confucian poetic yuan reflects the socio-political and psycho-sentimental aspects of relationships between people in Chinese society. In terms of subject matter, weakness, injustice, scandal, failure, frustration, anxiety, discordance and sorrow are just some of the problem topics considered and rendered poetically from this view.

With the expectation of both authenticity and sincerity of expression, in Confucian logic, the critical aspect of poetic expression arises from the principle of human-heartedness that works towards the good of society … otherwise poetry becomes a mere verbal exercise … hence losing its value for aesthetic education.

4. Outro

The technical art of composing and/or performing poetry (the other poetics) is anchored in these four inter-related conceptual fundamentals: poetic xing, poetic guan, poetic qun and poetic yuan, with poetic xing being the most important because it is integral to art and artistic effect:

If poetry is not appealing enough to inspire (xing) or move the reader emotionally,

it cannot evoke a reaction nor an aesthetic response (Wang, K. 2008, p17).

This traditional genre of Chinese poetry is constructed and designed to express and communicate a range of feelings, ideals and events in terms of a complex Confucian aesthetic discourse. Described by Wang Fuzhi (in Wang, K. 2008, p16), here is a closely paraphrased version rendered in poetic form so as to separate the conceptual ideation into its four constituent themes:

What is inspiring (xing) can be reflected (guan),

thus making xing more profound

What is reflected (guan) can be inspiring (xing),

thus making guan more obvious to the eye or mind

What is communicated (qun) leads to gentle criticism or warning,

thus making yuan more unforgettable

What is admonished (yuan) leads to communication (qun),

thus making qun more sincere and authentic.

___________________________________________________

Bibliography

Wang Keping (2008) Spirit of Chinese Poetics (Foreign Languages Press: Beijing). (English language edition) pp1-17, p231

Chinese Poetics in Green, R. and Cushman, S (Eds.) (2012) The Princeton Encyclopaedia of Poetry and Poetics (Princeton University Press: Princeton and Oxford) (4th Ed.) pp238-241

Further Reading

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: a social critique of the judement of taste (1979). Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating the photographs, using or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Please refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2025. CP in Mongolia. This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 30 April 2024. Last updated: 30 April 2024.