This short article presents a perspective from which other practices of contemporary Mongolian women in Mongolia may be considered. There is no understanding the present without a broader socio-cultural understanding of at least some of the past and how it may flow into the present.

Anyone who has spent any time with Mongolian people and their families in Mongolia will appreciate how much of what they do is an inter-generational family enterprise.

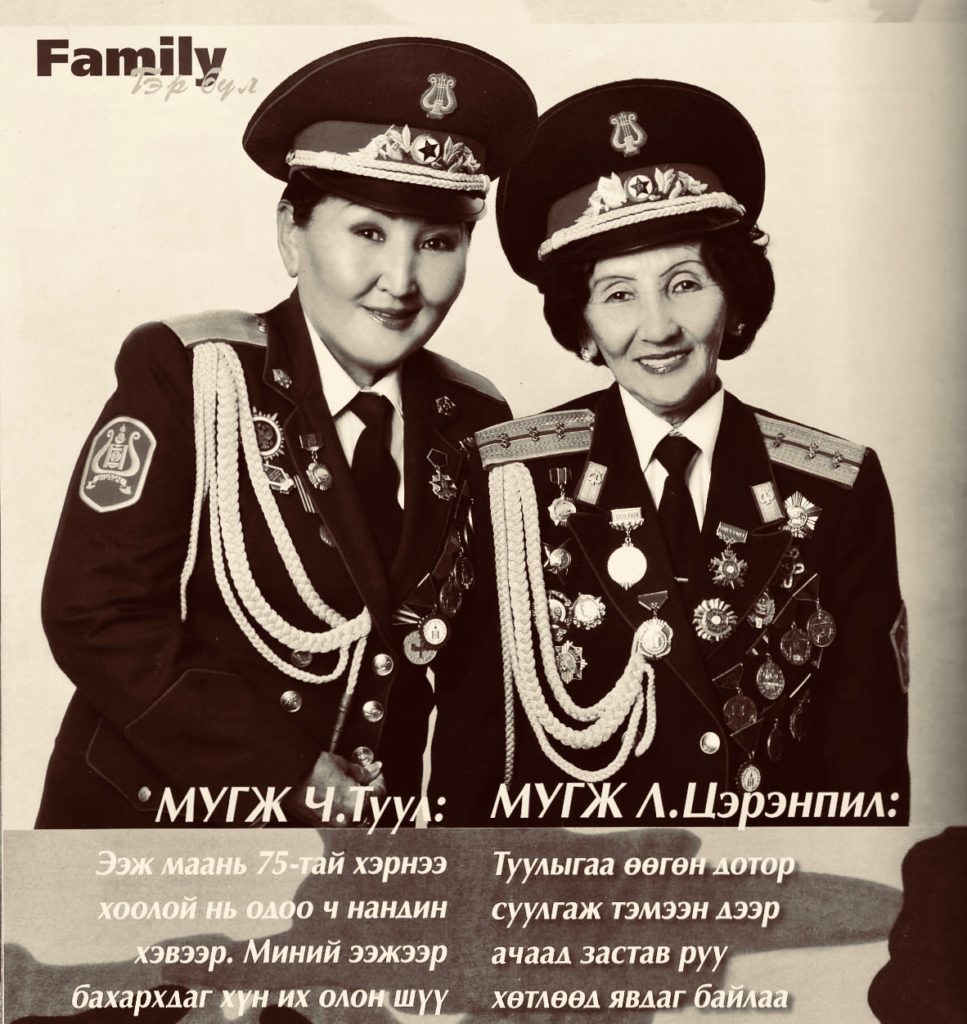

Back in 2008, the magazine Family became available to Mongolian women who had the resources to obtain a copy [i]. Whilst we in ‘the west’ are used to the ubiquity of such women’s ‘mags’ (Woman’s Day, Woman’s Weekly and New Idea just to name a few of this ilk in Australia), in Mongolia such hardcopy glossy publications had only just begun appearing in the many small kerbside vendor stands (that also sold cigarettes, SevenUp, shoelaces and apples from Russia) at the time. We are also less accustomed to seeing women in their army garb. However, such presentation in Mongolian-in-Mongolia society is more usual than not.

In 2008 Mongolian co-habitating multi-generational households still tended to have little discretionary disposable income to spend on a small luxury item such as a glossy tabloid magazine. Living in a ger or soviet-style apartment, in terms of expenditure, their priorities were the books and other equipment essential to their children’s primary and secondary school education, petrol (to pay for their own use of what was usually a shared car) and food for the family (which was purchased at small fresh food local markets, and not from one of the Nomin chain of supermarkets that at the time stocked mainly processed goods with a long shelf-life (such as instant noodles) imported from China and pickled ogorki (cucumbers) etcetera still bottled in Poland or Russia.

No surprises here. Nomin Holdings department store purchases were for international tourists; from China, Russia and further abroad. Mongolian women, however well-off, are responsible for managing their household budgets. They could get their tugriks (local Mongolian currency) to stretch much further elsewhere.

What did surprise me at the time was how women had begun looking to the (aspirational) images portrayed and promoted in these magazines—instead of to one another—as a means of socially-referencing and situating themselves. The dissolution of previous notions of local community and social standing had commenced. This was exacerbated by increasing rural to city-centre migration. The next iteration of image-making had arrived. Situated in their midst, whilst I was ‘observing’ them, doing my research, their attention was being drawn to new ‘objects’ designed by other forces who were now depicting them. So too with the introduction of television. They were transfixed. With what? I am still not sure. I should have asked even more questions at the time. Instead, I contracted my role to that of a more passive observer. So widespread and profoundly intrusive was this new media-driven wave of social change.

In retrospect, this neo-colonisation by globalising media organisations wasn’t so unusual right? Ten years on (2018), Google and now-nuanced brand differentiation, product placement, celebrity endorsement and niche marketing is the norm.

Question: But what was ‘the product’ being promoted by the magazine here at the time?

Question: Is it cultural reproduction? Or innovation at play?

A Cultural Studies class could spend a whole day unpacking the many narratives embedded in this Mongolian tabloid’s cover page, but for our purposes and for brevity, an introductory interpretation may have to suffice.

In 2008 such a depiction of inter-generational Mongolian womanhood was indeed a socio-political innovation, setting aside for now discussion about the glossy magazine format as the initial primary mode of promulgation.

The above image[ii] is indicative of an important ‘meme’ (a term first coined by Richard Dawkins in 1976) being promoted to Mongolian women by the emerging tabloid press in the local cultural environment at the time.

This front cover of the 2008 issue of Family represented a particular embodiment of cultural and other continuity-transmission between a (socialist era) mother and her (post-socialist era) daughter/s. There’s information about the differentiation between these two categories of Mongolian womanhood adopted for my research in other posts.

In terms of a situated continuity, it can, amongst other narratives, be interpreted as indicative of the transition away from a socialist era idealisation of Mongolian womanhood towards a post-socialist political and cultural (re)construction of the Mongolian-in-Mongolia social strata and its new world; one with which contemporary Mongolian women were being encouraged to identify yet still firmly anchored in the secular recent past.

The army uniform (a still important social and figurative expression in Mongolia) serves as the engaging metaphor for inter-generational continuity. The narrative arc of the magazine’s article and additional photographs inside go on to detail how each generation’s ‘success’ is reflected. The centrality of family and (professional) service to community are foregrounded albeit in different ways.

Both mother and daughter’s uniforms are decorated with many medals. In Mongolia, such medals reflect institutional recognition of individual and varied contributions to the social, cultural and familial good. Together, the accumulated tally of medals is considerable.

Each medal tells a different story. This was 2008. Purchased designer goods from Gucci, Lacroix, Fende and a Hermes handbag had yet to arrive as the preferred more modern-cosmopolitan indicative accoutrements of a ‘prospering’ Mongolian womanhood.

Interestingly, whilst the modalities of service may have changed to align with emerging local social change and reconstruction imperatives, social status and wider recognition constructed through the award of medals (a Soviet socialist innovation) to women and men continues to be the valued and done thing in circles of Mongolian society today. [iii]

Footnotes

[i] I use the word ‘resources’ because paper money was still scarce. Women were active participants and protagonists in kinship networks and other local economies of sharing (material goods) and exchange.

[ii] The mother and daughter pictured on the cover of the 2008 issue of Family were well-known in UB social circles at the time. Neither, however, is an active contributor to my own research. The text on the front cover is rendered in Mongolian (not Russian) Cyrillic script. To the best of my knowledge the reproduction in sepia of the front cover for strictly educational and non-commercial purposes does not infringe copyright.

[iii] I too have been honored with a medal, just the one. Be in no doubt, the recognition it represents is a beautiful thing.

Landscape 07: In the Family 01 was researched and written by Catherine Pleteshner.

For a consideration of idealised images of Mongolian womanhood during the soviet socialist era in Mongolia see Artscape 07.

See the INDEX to my blog for other articles that may be of interest.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating the images or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2024. CP in Mongolia. This post Landscape 07: In the Family 01 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 28 August 2018. Last updated: 20 June 2022.