Photographs by CP reprinted here with permission of B.Enerel.

A ‘next generation’ Mongolian-in-Mongolia artist: Bold Enerel

Enerel (see below) is the daughter of Mongolian artist Sukhbaatar Gantsatstral. They live together in Ulanbaator. At the time of writing, Enerel is approaching her 27th birthday and like her mother, has now also graduated as a formally trained artist from the Mongolian Art College in Ulanbaator.

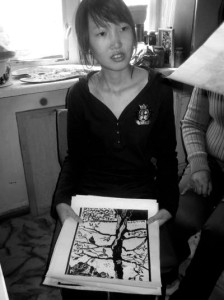

B. Enerel with one of her woodblock prints in the studio she still shares with her mother at the Mongolian Union of Artists’ (MUA) building in Ulanbaator 2008.

Daughter and mother, so obviously close in heart and mind, speak easily and mindfully, each to the other. Since we first met in 2008 I have observed how the volume of their ongoing conversations rarely rises above that of a gentle (yet not secretive) whisper, wherever they are and with whomever else they may be.

Thoughtful, meticulous, graceful and ever-careful with her spoken words, Enerel is literate in two of Mongolia’s languages: the traditional Mongol Bichig as well as the more modern Cyrillic form. She is currently at the advanced stage of studying English. The Korean and Japanese languages are next on her to-do list. It is therefor no surprise that Enerel is quite capable of articulating initial impressions of Lobsang Dargey Zava Damdin Lama (1976– ) in her own words: From the very beginning, my Teacher seemed a very respectful person and I felt deep respect for him. He has always treated us all very kindly. In one of our conversations, she went on to recount how Bagsh was organising his first art exhibition at the Mongolian National Library in Ulanbaator. He encouraged me to submit an original work of art for the competition. In terms of my art, my mother has always supported and encouraged me too. This was the summer of 2007, and the art exhibition-competition in Ulanbaator was an integral part of Zava Damdin Bagsh’s 140th Anniversary Birthday Celebrations. These were held in public venues and convention facilities, not just in Mongolia’s National Library but also over a period of seven days all over Ulanbaator.

Enerel was, at that time, 17 years old and only in her first year of Art School: Whilst thinking about what I should paint for the competition, I was at the same time reading a copy of Bagsh’s most recently published book, Hor Choijin. For her entry, she manifested an idea from an extract of this book written in Mongolian Cyrillic and poetic form: a work on a small piece of paper using an ink pen. It depicted the vast steppe of the Gobi.

My entry won a ‘Special Commendation.’ After the exhibition, I presented it to Zava Damdin Bagsh as a gift. This was my first artwork drawn from Mongol Buddhist poetry and perspectives. Memories of participating in Zava Bagsh’s exhibition-competition in 2007 still give me a lot of confidence, encouragement and joy! Inspired by this first exhibition success, I soon produced two more works, one of which was exhibited in China. The other was shown in the USA. For that exhibition, I sent my graphic woodblock print titled, ‘Queens and the Mongolian Way of Life’ (see below). To China, I sent ‘Tree.’

‘Queens and the Mongolian Way of Life.’ Woodblock print by Contemporary Mongolian Artist Bold Enerel (MUA Studio, Ulanbaator 2008).

The same materials and woodblock printing techniques were used for both works. I use a very sharp crafting knife. First, I think of the style of the work and paint it on paper. When the image is finally ready on paper, only then do I begin to work on the wood. I stencil the design onto the wood, and then begin carving it.

The timber has to be of excellent quality. It must also be cleaned thoroughly before the process of carving begins. The actual final size of the print comes from the one single piece of carved wood. When the carving on the wood has been completed, the prints are made using paint especially formulated for this purpose. Multiple copies of the print are then made, and only the finest copy, amongst many, is then selected. ‘Muutuu,’ a course-grained Chinese writing paper, is used. Working with wood to produce woodblock prints is quite complicated.

Another of Enerel’s woodblock prints won first place amongst the students at the Art College where she was studying. At a Japanese Mongolian Artists exhibition, her work also won 1st prize.

All enquiries to B. Enerel at: eneehe_smile06@yahoo.com

Author’s note: This vignette is a revision of an earlier draft. This is one story from a larger collection of written narratives about contemporary Mongolian women and aspects of the cultural and social worlds within which they are individually situated. (Pleteshner, C. 2011. Nomadic Temple: Daughters of Tsongkhapa in Mongolia. Zava Damdin Sutra and Scripture Institute, Ulaanbaator. Unpublished manuscript). Each vignette is grounded in ethnographic fieldwork and interviews with the person about whom I write. All of the people in this assemblage are Khalkha Mongols, the largest group of ethnic Mongol peoples living in Mongolia today. I would like to thank D. Gerelbayasgalan for the considerable effort she put into formally transcribing recordings of some interviews conducted with Mongol women across the country in 2008. Vignettes in the CPinMongolia.com series are grounded in these and other Mongolian women’s voices. Italicised text has been used to render their own words. B.Enerel would prefer that her given name (and patronymic) were noted here instead of a pseudonym.

Attribution

In keeping with ethical scholarly research and publishing practices and the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, I anticipate that anyone replicating the photographs or translating into another language all or part of this article and submitting it for accreditation or other purpose under their own name, to acknowledge this URL and its author as the source. Not to do so, is contrary to the ethical principles of the Creative Commons license as it applies to the public domain.

end of transcript.

Refer to the INDEX for other articles that may be of interest.

© 2013-2025. CP in Mongolia. This post is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Documents linked from this page may be subject to other restrictions. Posted: 2 October 2015. Last updated: 29 October 2017.